Africa – Exploring Cameroon

We left the accommodation at 0700 and drove with our escort back to Port Harcourt international. Our marshaller was there to greet us, and took us to passport control for the exit formalities. For only the second time since the start of the trip, a bribe was demanded; the immigration personnel would not process our passports unless we made it worth their while. A tip to people for good service is one thing, but $90 was being asked for here. We decided to go to the aircraft and take care of all the other paperwork before returning to deal with them. Filing the flight plan took forever; in a new twist, we even paid a visit to the approach controllers to get their blessing before the plan would be accepted. I decided not to ask them why they’d vectored us out to the delta and back on the way in.

After the commercial department had once again recalculated the fees (thanks, Sky Watch) I returned to the aircraft to see how Sophia was faring. An immigration official had come out to the aircraft with stamped passports and there was now a stand-off ongoing as to how much would be paid for their return. With the intervention of our marshaller, and some hard bargaining on the part of Sophia, the “fee” was negotiated down to about $6. A speech from our helper about how we were unpaid volunteers here to look after the women of Port Harcourt seemed to help, piling on a bit of guilt for demanding a bribe. Finally, we were cleared for taxi and on our way to our next country, Cameroon.

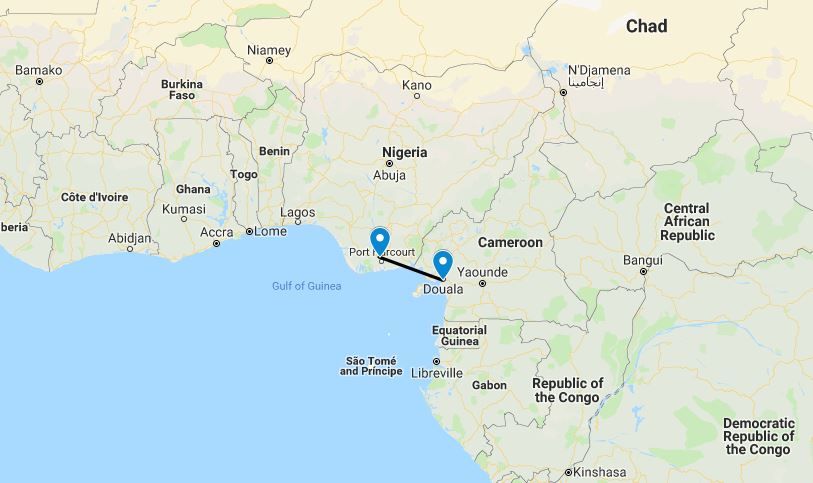

At 170 nautical miles, the flight was not particularly long. We flew along the coast, passing over a large oil export facility that had been carved out of the endless jungle. Judging by the lush vegetation all around, and encroaching onto, the facility, it was not having an obvious negative impact! At the border, Port Harcourt approach told us to contact Douala; this turned out to be easier said than done. The low-altitude airway from Port Harcourt to Douala mysteriously vanishes at the border, for Cameroon has a surprise in store for the unwary aviator; the 14,000ft Mt Cameroon sitting slap-bang in the middle of the route. At this time of year it was of course shrouded in cloud, and it would be all too easy to simply fly on through the cloud before receiving a rude awakening. Flying along as we were at 9,000ft, with the mountain towering above us, it was easy to see how people could go astray. While we’d been aware of the peak well in advance, I was very happy to have my Garmin GPS with terrain data (and terrain warnings, come to that). As a last line of defense, it will flash up terrain alerts two minutes before a possible conflict, as well as display a cross section of terrain heights along your route.

Mt Cameroon blocked any communication with Douala, so we decided to use our initiative and followed the coastline south to a point where radio contact was possible. The first thing Douala said to us after I reported our position and altitude was “Do you know about the mountain?!” We reported that yes, we did know about the mountain, and promised to fly around it. Reassured, Douala gave us arrival instructions as we flew down between Mt Cameroon and the 10,000ft peaks on the island of Malabo, and made our way onto the standard arrival and VOR approach into Douala. It was clearly the rainy season; the terrain below us was inundated, and even the suburbs of the town clearly sodden with the creeks close to overflowing.

We were directed to park at gate C1, right up against the main terminal building, where our little Skylane would be staying for the next four nights. Sophia’s contact here, Dr John, had managed to talk his way out onto the tarmac wearing a borrowed high-vis jacket and was waiting with a policeman to receive us. After a warm welcome, we were led the 50 meters to the VIP salon where we filled in our entry forms and had our passports stamped and from there to the main arrivals hall and our ride into town. A room had been arranged for us at the Royal Palace, and Dr John had excelled himself; we would be staying in a large comfortable room with two big beds and even, much to Sophia’s delight, a bath tub!

After leaving us to rest for a few hours, Dr John and his good friend Ignacius returned to take us out for a drive around Douala. It was a busy, bustling city with an active port, and a nearby “criminals roundabout” where apparently people who had stolen things at the port went to sell their goods! We passed by a number of the government buildings, as well as several hospitals, before ending up at an outdoor restaurant overlooking one of the swollen creeks. It seemed to be a high end establishment with several French expat families, and local citizens celebrating special occasions. There was even a party of nuns enjoying themselves out at the end of the deck.

Our first port of call for the day was a medical supply store in the centre of Douala. Over dinner the previous night it had been decided that, while we could not meet the original demand of paying people to attend the training sessions, we should purchase a sizable donation for the hospital; in this case, a caesarian section kit. Sophia’s sponsor had given us a list of countries where, due to government regulations of the countries in question, we could not donate the blood-pressure monitoring machines that we carried, and Cameroon was one of them. It seems a shame that government bureaucracy prevents the donation of simple, essential equipment to people in need.

In the end, the “quick” visit to the medical supply store took about three hours. It was housed in a small warren of rooms above a row of shops, and like most building’s we’d seen the build quality and maintenance was very poor. Small cardboard boxes full of equipment were jammed into haphazard mountains on shelving around the main room, which did not seem to speed up the process of finding equipment. A full hour was spent in the writing up of an elaborate receipt for what had been purchased.

From here we paid a visit to the Catholic hospital that Sophia would be giving training at the next day, to introduce ourselves and finalise the plans. Dr John took us on a tour of the facility, introducing us to almost everyone who worked there; everyone was warm and welcoming. Plastered around the facility were photocopies of a crude poem, “The abortion tree”, written in the voice of a baby decrying how she was “murdered” and “thrown away”. It was tastefully illustrated with a drawing of dead babies hanging from a tree. It was disturbing to see religious superstition being given such prominence in a medical facility; the recent case of a mother dying in Ireland because their Catholic-fueled abortion policy denied her a life-saving procedure demonstrated tragically how superstition should not be allowed to over-ride sound medical science.

After a visit to an internet cafe to spend an hour catching up on work, we stopped by a small restaurant in town for dinner. It was made up of a few tables in a courtyard, with a large grill at one side roasting every single edible part of the chicken, as well as some other items that were vaguely described as “meat”. We were, thankfully, presented with two large plates of what was clearly identifiable as chicken, accompanied by roasted plantains; it all turned out to be delicious.

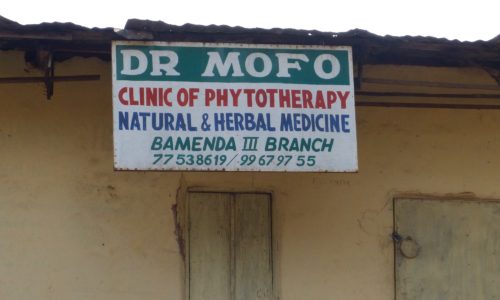

Today was the day to head North, to the regional city of Bamenda. Dr John had originally been planning to come with us but, with his young daughter sick with malaria, sensibly decided to stay behind. In his stead, we had been put in touch with two residents of Bamenda, both medical men, who were related to a colleague of Sophia’s back in the UK. We ended up leaving the hotel rather late with Ignacius who accompanied us out to the airport. He had determined that if one visited a desk upstairs in the terminal building, and spoke confidently, it was possible to walk away with a temporary ID badge that would allow you to access all areas. He quickly stepped into the role of handling agent and strode through the terminal with us in tow, directing people to assist us!

Douala turned out to be at the “complete pain in the neck” end of the scale when it came to leaving. It took a good half hour before anyone could even direct us where to start the process of filing a flight plan. This was carried out in one office, carried to the Cameroon CAA office for a stamp, and one then had to ferry it out of the airport to the control tower a short walk away. Here it was checked, directed to another office for payment, returned to the base of the tower for filing, and then taken upstairs for the weather briefing. Naturally, none of these steps were quick, and by the time we made it back to the aircraft several hours after arriving the afternoon thunderstorms were building and there was still one more bill to pay. This bill had something wrong with it and they’d need an hour to fix it. With the weather being just too bad now to gamble with, we packed it in and headed to the Douala Ibis to wait out the night, and try again the following day.

Determined to avoid the delays of the previous day, we started early. The hotel let us know that the shuttle bus was outside, so we headed out and climbed aboard. After a few minutes it became clear that we had one less seat than we had passengers. Shortly afterwards it became clear that this was not in fact the shuttle bus at all, but simply another bus that had come to pick up a number of members of a western company who were driving to another part of the country. It was lucky that they hadn’t had another free seat, as no-one had thought it odd that these two strangers were there; who knows where we’d have ended up when the bus drove off with us on board.

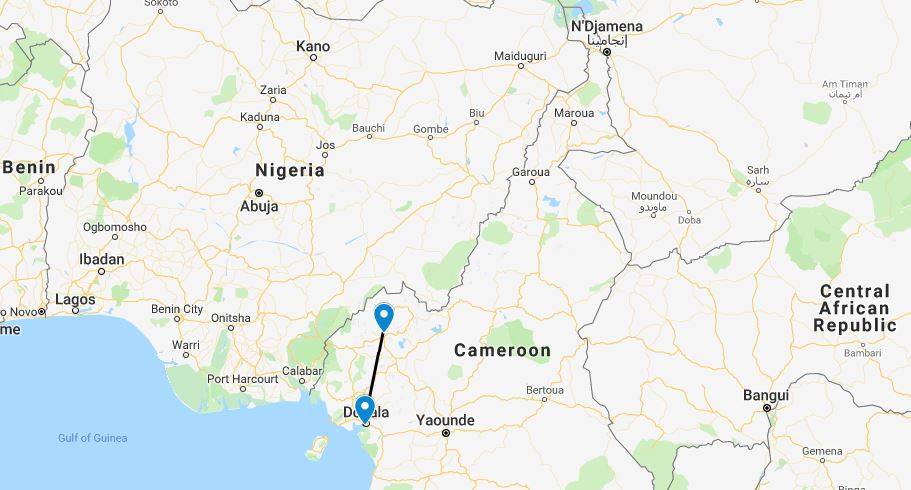

We went back to reception, who were very apologetic, and located the correct bus for us. Having been through the rigamarole of departing the airport once already, we managed to file our new flight plan and pay our final bill in little over an hour, and were soon winging our way north. The “minimum safe altitude” assigned for IFR flight in this area was 17,000ft, an altitude that we could only dream of, despite the highest peak along the route being only 8,000ft or so. We were cleared to fly at 9,500ft, under visual flight rules, and made responsible for our own terrain clearance. As we headed north away from Douala the land slowly rose towards the 4,000ft level of Bamenda, but between Douala and our destination were a ridge of 8,000ft mountains to clear.

As we reached this mountainous area we lost contact with Douala, and switched over to the Bamenda frequency. Repeated calls went unanswered, so we self-announced on their frequency as we did a fly-past of the runway to check the condition and wind direction, and touched down on runway 36. With a fairly long runway, we were able to slow down and turn off before we reached the second half of the runway where people appeared to be wandering around and driving motorbikes. We parked up in front of what looked like a terminal building, but turned out to have been commandeered as a military base; no commercial flights came to Bamenda any more.

A few men in military fatigues wandered over to say hello. One of them requested a copy of our manifest which I handed over, and he suggested we go and check in with the civilian authorities at the other end of the apron. Here we found the airport manager, who welcomed us and took another copy of the manifest. While we waited for our hosts, he also inquired about our departure plans so that he could ensure that someone would be around to accept our flight plan. Once our hosts arrived we double checked with the authorities that our aircraft would be OK where it was, and headed to see the regional director of health.

The director was very welcoming, and seemed fascinated by the project. He quickly fleshed out a program of four locations that Sophia should visit to get a good idea of the varying medical facilities in the area, and drafted a letter of introduction for us to assist with each of the visits. From here we headed a little further up the road to visit the regional hospital where our hosts worked. The director, who was rather reserved at first, became much friendlier and more enthusiastic after reading the letter of introduction and hearing what the project was about; he agreed that we could organise a teaching session for the next day.

After a stop at the midwives’ office to introduce ourselves, we passed by the day hospital where one of our hosts, Raymond, was on duty; he was in consultation with the wife of a German doctor who was working at the hospital, and had brought her young son in to be checked for malaria; he didn’t look well at all. She was kind enough to suggest some interesting activities around Bamenda for our proposed day off on Saturday.

Raymond came to collect us from the hotel around 0900 on the Saturday, with his friend Kenneth, who worked in IT at the hospital. We drove out of the city of Bamenda towards a village that housed a Catholic hospital, which coincidentally was the beginning of a network of trails leading up into the hills. After a couple of false starts, as things had apparently changed since he was last there, we set off up a small track with a distant peak as our intended destination. Given that we were starting from 4,000ft above sea level, the temperature was not as hot as it had been down in Douala. This was a very good thing, as with the steep trail and humid air we were soon over-heating anyway!

The trail passed through a tiny village of 4 or 5 buildings, before continuing along a tiny track that serviced a small water pipeline coming down from the hills. At times we were more climbing than hiking, and after a final scramble we found ourselves on top of the first hill. The views back over the hospital were already fantastic, but we were not yet anywhere near our final peak; after a moment to catch our breath Raymond led us on through a barbed wire fence and struck out cross country, along what he thought was probably a shortcut.

The trail vanished shortly after we passed a small quarry where people had been digging rock out by hand for use as gravel on paths, and in construction. We scrambled up various rocky outcrops, before coming to the top of the small waterfall that we’d had our eye on during most of the climb up. The stream appeared as if from nowhere out of a thick tangle of vegetation before plummeting over the side of the hill. It was decided that the only possible way to continue was by removing shoes and socks and wading the stream, at the top of the large waterfall. I wasn’t entirely convinced that this was a good idea, but in the end it turned out to be significantly more straightforward than we had feared.

From here we soon found a trail again; right at the point where it bridged the stream we had just waded, in fact. We continued uphill and came out onto a crest; the peak we were aiming for was visible across a cultivated section of land. Raymond assessed the final hill, now that it was more clearly visible, and decided that it looked pretty tough and that we’d head back instead as we were already late for lunch. Fair enough. Raymond’s shortcuts were rejected this time in favour of the longer, but faster moving route along existing tracks which snaked around the hills and back down to the hospital.

As we headed down, Raymond was telling me about how all the previous four times he’d walked here he’d ended up soaked by rain, and how lucky we had been with the weather. Predictably, moments later a huge grey wall of water could be seen moving quickly towards us along the side of the hills, and within minutes we were soaked to the skin. We made our way as quickly as we could towards the bottom, and shelter, but the trails had turned slick in the wet and little streams of water built up remarkably quickly along the paths we were taking. We ended up taking cover under an abandoned trailer; we were already soaked through, but wanted to try and protect the phones and cameras before they were ruined beyond repair!

The rain ended as quickly as it had started, and we squelched back to the car. After a short stop at the market to buy Sophia a simple skirt (she had no dry clothes at the hotel) we made the hour’s drive back to the Azam Residence to change into dry outfits before going for our lunch appointment; we arrived here, finally, at 4pm. Dinner was at Dr Mbu’s home, with his wife and baby daughter; Raymond, his wife and baby son also joined us. We were served traditional Bamenda fare, the details of which now escape me, but shrimp and fish were involved; Sophia questioned how shrimp had become involved in the traditional dish when we were so far from the sea, and we were informed that they were apparently caught, dried, and transported inland.

Most of the entertainment during the evening was provided by the two babies, one of who could just walk, and the other of whom was getting close. Their interaction was fun to watch! Dr Mbu quizzed us about television preachers, and was astonished to find that we had not heard of any of the ones he named. We were given a quick rundown of the major televised preachers to bring us up to speed, before Raymond gave us a lift halfway back to the hotel. The remainder of the journey was carried out on motor-taxi; apparently the old drivers are the one to choose, as they have survived a long time and must therefore be safe.

Raymond collected us after breakfast and we headed out to the airport. The lady from finance was there to collect our additional day’s landing fee. No-one was there to process a flight plan, but the lady said that was no problem; we could leave it with her, and she’d give it to the right person the following day. I couldn’t help but feel that this rather defeated much of the point of filing the flight plan to begin with. When I headed out to join Sophia on the apron, I found that the morning’s activity at the military base had evidently reached a lull and most of the recruits were now gathered around the aircraft, quizzing Sophia all about it as she tried to get herself ready for departure.

The recruits were all very friendly, although for some reason convinced that we must have whisky with us that we could give them. In the end, they were satisfied with a tube of Pringles; I’m not sure how far it was going to go between 30 people. They told us that most of them were there temporarily to ensure that things remained peaceful during the impending elections. Numerous photos were taken of them posing with us and the aircraft, and after accepting that we could unfortunately not take them all for a flight, they backed off as we started up and waved goodbye as we taxied out for departure. As we took off I made sure to do a low fly-by over the apron to wave goodbye!

Due to a lack of fuel at Bamenda, we first headed back to the South for Douala. There was a lot of cloud around, and Douala was reporting thunderstorms; however, there was no activity at all on the storm-scope so we pressed on and found that there was no evidence at all of any storm around the airport. This time we were directed to park as far away from the terminal as it was possible to park, at the end of the freight apron, and Sophia and I set off to transit Douala airport in record time. Having already done it twice, we at least knew exactly where to go!

By now the people in the tower recognised me, and everything went smoothly. The only hang-up was the fuel; we had to wait for a Kenya airways flight to be refueled, and then managed to intercept the fuelers who were off to fetch the AVGAS truck and let them know that we would in fact be needing jet fuel. We refueled from a large, camouflage painted military fuel bowser, and as soon as this was completed we started up and set off north to Garoua. This would be an essential fuel stop, as well as a place to clear immigration, before moving on to Chad; neither of the airports we’d visit as we traveled across Chad had fuel available.

The flight to Garoua seemed long, but only because we’d become used to short hops around Nigeria and Cameroon. Thunderstorms were visible on the storm-scope as we went, but as forecast everything moved away to the west or dissipated before we reached it. We flew at 9,500ft, and it felt like we just squeaked over the final, 8,000ft mountain range before Garoua despite having a good 1,500ft of clearance between us and the peaks. As we descended into Garoua we passed over a large river, swollen and filled with sediment by recent rains. This, it turned out, was one of the upper rivers feeding the river Niger; it flowed north, then west, and finally south again to meet the sea in the Niger Delta where we’d been a few days before.

Garoua, a mid-size airport, was almost deserted when we arrived. The only other aircraft around was a South African registered Cessna Caravan set up for aerial survey. We were marshaled into a parking spot behind it where it was possible to tie the aircraft down, in case of strong winds; this was a rare option in the places we’d visited to date, and provided a certain amount of peace of mind. We were met at the aircraft by a pair of military officers who inquired as to our business, but seemed entirely unconcerned by our arrival. On hearing that we needed a place to stay, the Commandant volunteered his services to take us to a hotel, and we set off into town ending up at the “Dreamland”; basic, but very cheap at $25/night and equipped with air conditioning and wifi!

Click here to read the next part of the story.