Africa – Around Nigeria

On the morning of departure Sophia and I split up to cover more ground. She had visits to a third hospital, and also the Ministry of Health, to participate in so I elected to head to the airport and take care of the paperwork and fuel so we could make a swift departure when Sophia arrived. The hotel shuttle dropped me at departures, and I began my efforts to get through the airport without the help of a handling agent. Given how easy arrival had been a couple of days before I was not expecting much in the way of trouble, but unfortunately it was not to be as simple as we had thought.

The airport police were happy to let me into the building but when I tried to get through passport control, they were confused by my lack of a handling agent and sent me off to Menzies. Menzies ended up being incredibly helpful; the manager walked me through security and had someone drive me to the control tower, all for no charge. Our fees were, once again, minimal; around $15 for landing and parking. After more than a month of “Cash only!” it was a surprise to be informed that they only accepted credit cards. No-one could tell me how to call the fuelers, but they could tell me where they were located, so I headed over to their office and tried to acquire some Jet A. They were at first insistent that I move the aircraft to the underground fueling point near the terminal, but upon finding out that I only needed 100 litres they changed their tune and told me to leave it where it was. I walked back through the military zone with no trouble, and waited.

Killing time waiting for the fuel to appear, I pre-flighted and checked the oil. The oil usage was holding steady at around 100ml/hr, and was giving me much more confidence than when we’d been burning nearly double that back in the desert. Hearing a vehicle approaching, I looked up to see a ropy looking tractor headed towards me, towing an even ropier looking trailer. The driver was not too hot at parking; eventually giving up trying to get the trailer into position he just unhooked it and with the help of his colleague pushed it into place. No ladder was needed; he just climbed on top of the Jet-A tank on the trailer and got to work. While the driver filled, his colleague cranked the handle of the manual fuel pump. It was slow work, but eventually the tanks were full.

In the meantime, the professor had called the head of the airport to try and ease Sophia’s passage through the terminal on her arrival. A smartly dressed man in a suit turned up and roganised a truck to take me back to the terminal, where I changed all our remaining currency into dollars, and then back out to the aircraft to wait for Sophia. I settled down to read, but after only moments I was interrupted by a man who had come down the steps of the Falcon parked next to us and wondered if I’d care to join them for a drink. I certainly would! Minutes later I was relaxing in the cabin of the Falcon, drinking tea with the pilots and the air hostess who had come to get the aircraft ready for a flight the following day. They were French, working on a two-week rotation where they’d be on standby for the customer in Benin in case he wanted to go somewhere. They’d been here for a week so far with no flying and were looking forward to doing something.

Eventually Sophia appeared, clutching packed lunches that the professor had insisted on sending with her. Perfect! Minutes later we were taxiing for departure, and cleared for take-off. Departure clearance was to track the VOR outbound to the southeast until contact was established with Lagos approach, who seem to control the airspace about about 10,000ft over Benin and Togo. As it turned out we climbed so slowly compared to the usual jet traffic in and out of Ghana that we were getting nowhere with Lagos and were told to talk to Togo instead; being rather close, we could at least hear them and they could hear us. We followed the shore for some time, and received permission to stop our climb at 7,000ft. The flight was only 60 nautical miles, so there was no point in going higher.

Lagos approach, when we finally got in touch, were busy. Not surprising for one of Africa’s major air hubs. We were vectored around to the north, and lined up for an ILS approach on one of the two parallel runways. Airliners on 18L, and Cessna 182s on 18R, was the arrangement for a while. We were asked if we could go any faster; unfortunately, we were unable to oblige. It seemed that Lagos was not used to GA aircraft! We landed and quickly vacated the runway, being told to hold short of the connecting taxiway while an Ethiopian 787 Dreamliner taxied past. This was the first one I had seen; it was remarkably similar in appearance to any other airliner, and did not give quite the same level of visual excitement as the first sight of an A380. We continued behind the Dreamliner and were directed to gate E52. This was the first time I had actually been sent to a gate, and at the international terminal too. We parked up sandwiched between an A340 and a B777.

We were met at the aircraft by a junior representative of our handling agent, Sky Watch, along with a host of immigration police and other airport staff. I filled in several very similar forms about aircraft details and crew particulars, and eventually the host of people dispersed leaving only the immigration agent, chief handler, and Sky Watch rep. It turned out that immigration were demanding a “Gen Dec”, a form which we had never been asked for before. They didn’t have a template that we could fill in; you had to create your own and hope that it sufficed. We were also presented with the bill for navigation fees, which Sky Watch had paid on our behalf and then brought on to us; a ten second glance at the invoice, which included all the equations used to calculate the invoice, made it clear that it was completely wrong. The airport billing department had signed it off as checked twice, and Sky Watch had then paid it, evidently with no-one actually bothering to even look at the figures, which was extremely unimpressive. Our rep looked at it and agreed that it was totally wrong, but said that as they had already paid it then we had to pay them that amount; given that it was about $900 too high I declined and suggested we go and sort it out with the airport authorities.

This is where our quick immigration stop started to unravel. It became clear that the Sky Watch rep had really very little idea of what he was doing and we traipsed around several air-side offices, with him arguing with various police and immigration figures; they still would not even allow me into the building. Eventually he gave up and called the chief marshaller who had been very helpful; he came to Sky Watch’s rescue, organised access to the terminal for me, and even provided a template for the Gen Dec form. Some more messing around in the terminal and we eventually ended up in the office of the Head of Department, Commercial, for the Nigerian Airspace Management Agency. A senior member of Sky Watch had thankfully arrived. All agreed that the invoice was nonsense, but cautioned that to sort it out would take several days; I’m not entirely sure why. It was decided that we would continue with no fees paid, and the invoice issues would be settled later by email; this was fine by me. After reminding the junior Sky Watch rep that we’d need our passports stamped to show we were legally in the country, and waiting nearly another hour while he arranged this, we were eventually on our way several hours later than scheduled.

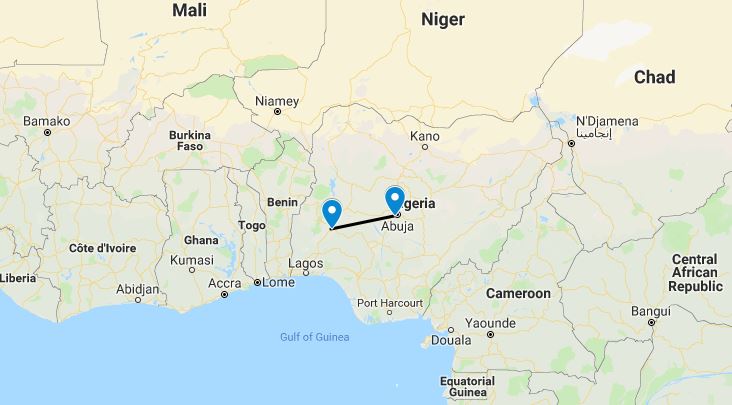

The delay had allowed convective weather to start building up, so the 140 nautical mile journey to Ilorin was not entirely straightforward. We departed again on runway 18R, and were told to continue south until given further clearance. Approach then seemed to forget about us and I was forced to drop the flaps and slow down to minimum speed to try and buy some time so we didn’t enter the prohibited zones to the south before we managed to get a change of course assigned to us. This was given as “proceed on course”, which would take us directly back overhead the airport. We queried this and ATC agreed that this was not ideal, so vectored us around the airport to the east before putting us back on course to Ilorin.

With several cloud layers, and thunderstorms starting to form, I placed my faith in the “Strikefinder” which the aircraft was equipped with. Plotting the location of lightning strikes within a 200 nautical mile radius, this instrument allows one to to navigate around weather in a strategic sense; using it to thread between individual cells is not recommended. It showed that the thunderstorm activity lay along our route, and to the south and east; as it happened, a diversion to the north would take us on a more direct route towards our destination and ATC granted this without any trouble. We were cleared to land straight in on runway 5; there was a slight tail wind but nothing that we couldn’t comfortably manage on a 2 mile long runway.

Ilorin could not have been more different than Lagos. There was only one other aircraft on the apron, a military transport. We were marshaled to park directly outside the terminal, but on learning that we’d be staying three nights tower suggested that the far end of the apron might be more suitable to be clear of the traffic that would be coming and going. Sophia left the aircraft to let the small entourage that was building up know why I was ignoring the marshaller, and I taxied over to park near the tower and shut down. We were greeted by police, who left satisfied after a short discussion about our meeting, and a lady from the airport authority who collected our $3 landing fee.

Aircraft secure, we walked over to the terminal where we were greeted by the extremely enthusiastic Dr Luther King Fasehun and his assistants from the Well-being Foundation in Nigeria. A cameraman was darting around snapping pictures of anything that moved, and plenty that didn’t. We were helped into a foundation SUV and driven straight to the Kwara hotel, apparently the best in Lagos, which the foundation had arranged to put us up in. I could well believe that it was the best in town; it was certainly the nicest place that we had stayed in so far. Having skipped lunch again we were soon to be found in the hotel restaurant, where the waitress seemed very happy to inform us that it was Chinese night. Sophia opted for traditional Nigerian food, but I found the evening’s special, cooked at the counter in the middle of the dining area, to be surprisingly good!

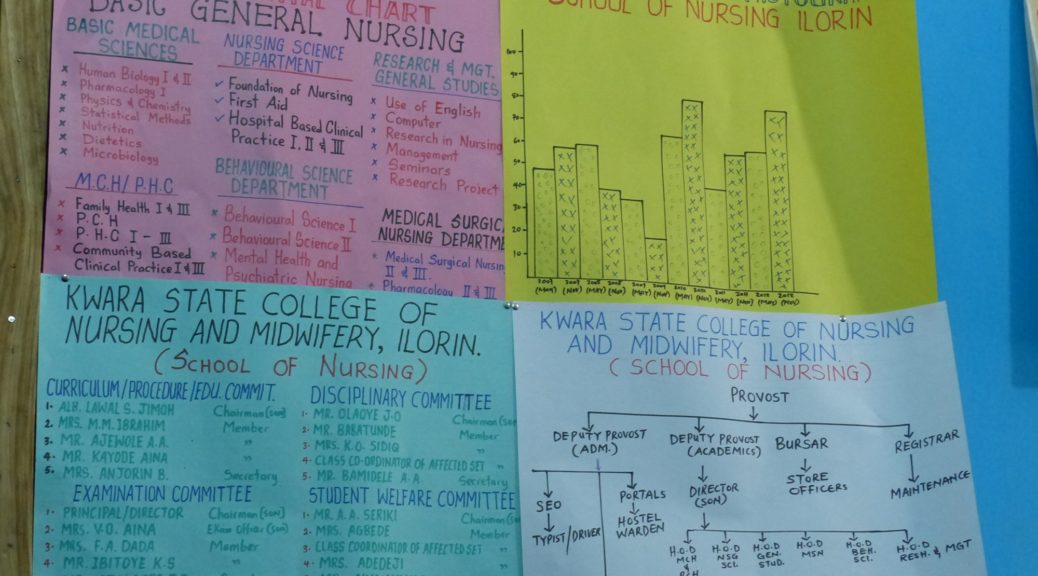

On Saturday morning Dr Fasehun took us to a local clinic for a tour and training session. It was located just a few minutes from the hotel, and was a fairly small location but with a good turnout of 20 or so nurses, all on their day off. They had in fact originally attended the day before, but the huge delays at Lagos had meant that we had not arrived in time to meet with them and Dr Fasehun had had to mollify them with drinks and snacks.

The morning’s session went well; it was good to be working in English again rather than French, and the absence of a projector meant that the training was conducted around a flip chart in a rather more intimate and off-the-cuff atmosphere. The “Mama Natalie” birthing simulator turned out to be a hit as usual, with patients from other parts of the clinic crowding around the windows to look in and take photographs of the practical training. The only sour moment came when the audience complained that Sophia had not provided them with project branded pens and notepaper for the session! At least that suggested that they were learning enough from the training that they wanted to write it down.

Dr Fasehun had told us that there was a VIP visitor in town, who was departing early on Monday morning. Apparently people had traveled from all over Nigeria for the chance of a meeting with this politician, and as a result the doctor was anticipating huge crowds at the airport as people departed again. It was therefore prescribed that we would depart the hotel a little after 6:00am to take account of any possible delays at the airport. As we were leaving the hotel we saw a private jet pass overhead; evidently the VIP was on his way.

On the journey to the airport Dr Fasehun explained that the foundation he helped manage was created by the famous politician’s wife, and that in fact the car and driver we were travelling in were paid for by him. This was why transport had apparently not been available the day before; the car had been shuttling the Honourable Minister around. One of the perks of this form of travel was that we were waved past the queue of traffic at the airport as VIPs, avoiding any delays. Once inside it turned out that there were no queues to deal with at all, as we had no need of check-in, and within minutes we were out on the tarmac.

The main terminal had a huge, new-looking control tower built into it; but it was apparently not in use and I left Sophia packing the aircraft as I headed to the old, ropy looking tower to take care of the formalities. We’d paid our $3 landing fee on arrival, so all that we had to do was file the flight plan which didn’t take too long. We popped back into the terminal to say goodbye to Dr Fasehun, who was waiting for his own commercial flight to Abuja, and departed. There was something wrong with Ilorin Tower’s radio; they were transmitting but all that was coming through was silence (you can tell they are transmitting as you can hear the “carrier wave”, but no other sound). They eventually sorted that out, but we could still barely hear them; the background noise of people talking and other, more peculiar noises almost drowned out the controller. Despite being informed of this by both us and the incoming commercial flight, the people in the tower seemed entirely unconcerned about doing anything to fix it (such as asking people to stop talking), preferring to compromise safety by remaining almost unintelligible.

We climbed out over Ilorin city. When flying over African countries many unfinished buildings can often be seen; people seem to build the walls, but stop before roofing it. Many seem rather over-grown, like they’ve not been touched in some years. Perhaps there is a good reason for this, but it seems like a huge waste of resources in environments which are not terribly wealthy. The suburbs of Ilorin seemed to have more unfinished buildings than completed ones.

Conditions were good for flying, with a low broken to overcast layer appearing an hour into the flight but breaking up by the time we came close to Abuja. The airport here was significantly busier than Ilorin, and we were marshaled into park down the very end of the general aviation apron which was crowded with private jets. A Sky Watch rep was here to meet us. Once again, they did not seem terribly organised and after we had taken our baggage from the aircraft he set about trying to find a vehicle to take us to the international terminal. He disappeared for a while and came back having had no luck, and finally responded to our pointing out that having arrived from Ilorin, maybe we could just walk to the domestic, GA terminal. As we waited, the commercial flight from Ilorin touched down with Dr Fasehun on board.

By this stage, he had however decided that we should take fuel now rather than on departure. I was happy with this, but became less so when it tuned out that we’d be waiting another hour to get anything done. Our rep once again had to walk off and talk to fuelers; the first ones he went to had nothing small enough to fuel us, but eventually he found someone with the right truck and told us they’d be along in 20 minutes or so. We had been hanging around on the ramp for so long by now that the Nigerian CAA had decided to take an interest in this little aircraft, and decided to conduct an impromptu inspection.

The CAA rep first examined the aircraft paperwork. Thankfully the aircraft owner had now supplied us with the required maintenance certificate, just a few days before arrival here, so our paperwork was found to be in order. He then turned his attention to the aircraft, but didn’t know very much about light aircraft so wandered around poking aimlessly at things before coming to something he knew; the lights. All lights were to be switched on and checked for operation; even the courtesy lights under the wings to stop you tripping over the wheels when getting in or out at night. I had never had any reason to even look at these, and had no idea at all how to turn them on; I tried all the switches that might have done so with no success so we concluded that they didn’t work. The CAA rep looked very excited at having found something to fail us on, before I located a section of the aircraft manual (supplied to us in French only) and bluffed that it described these lights as optional. After a long mumbled conference with his boss he decided that we were free to go.

With the aircraft refueled, we headed out to meet our contact here, Dr Fred Achem; the president of the Society of Gynecologists and Obstetricians of Nigera. He was an extremely warm and welcoming man, looking very dapper in a red bow tie. He had gone all out on our welcome, and in addition to his colleague Moses, he told us that he had arranged for “a lot of women” to greet us and that they’d be here any moment. “A lot of women” turned out to be 15 or so representatives from the Women’s Council of Nigeria, accompanied by a TV cameraman. They performed an official welcome for us in the car park, with the event orchestrated for the camera by Dr Achem, and activities having to pause now and then while everyone moved to let a car drive past. This done, the ladies decided that we should go and see the aircraft; the security rules of the airport demanding an ID badge be issued for any non-crew did not phase them.

A select delegation of ladies marched up to the security checkpoint and, after a brief discussion, convinced security that they should be permitted airside to do what they wanted. I think the staff were a little taken aback at being confronted by this group of strong women escorted by Dr Achem and his bow tie. Our delegation strode back to the aircraft, and it was decided that we should “arrive” again to catch it on camera; a few minutes later the aircraft had control locks and covers removed and we were pretending that we had just parked and exited to be greeted by Dr Achem and the group. The speeches were all rehashed for the camera, and everyone then settled in to have a good poke around the aircraft. I meanwhile had spotted a British registered Diamond DA42 light twin across the apron being fueled and could not resist wandering off to have a look.

It turned out to belong to a company that did flight calibration services for radio navigation aids such as VORs and ILS systems. The pilot, Stuart, told me that these should be done every six months but Nigeria hadn’t done them for two years or more. They’d just finished checking Lagos where apparently the accuracy of all the navigation aids could be summed up as “dangerous”, and were now working on Abuja. The DA42 seemed like the perfect aircraft for the job, with two aero-diesels running on Jet-A, and a modern flat-screen equipped cockpit with full autopilot. I was a little jealous, but drew solace from the fact that our Cessna was much more suitable for rough strips once we started visiting places without tarmac.

We drove from the airport straight to the hotel, about a 45 minute journey. Dr Achem ensured that we were comfortable (the hotel was even nicer than the one in Ilorin) before saying his goodbyes; he was headed straight back to the airport to catch a flight to Lagos for a couple of days. We immediately made for the poolside bar to have a bite to eat; it had been another lunch-less day, as was usual when flying. Moses came back to collect us after a few hours and take us for dinner at the “Africa-Asia Garden”. Apart from the odd bit of decoration the Asian side of this place was hard to detect. Apparently garden style places to eat had become trendy and were springing up all over town. The menu style was also exploding in popularity; you simply went to the kitchen and selected which catfish you wanted them to cook for you, from tanks full of them. Once you’d selected (they were priced base on size, separated into small, medium, and large tanks) they would catch the fish, smack it firmly on the head a few times, and prepare it for consumption.

On Tuesday morning Sophia and I again split up. Sophia went with Moses to a school of nursing about an hour away, and I was sent with a taxi driver to the Sudan embassy to get our visas for the visits to Darfur and Khartoum. We’d not been able to organise these in London as the required invitation letters had not been available, and apparently one could only have a visa issued for one month from date of issue in London, which was of no use to us at all given the time we’d be travelling for before getting there. We located the embassy without too much trouble, and then the fun began. The guards told us that visas were only issued on Mondays and Thursday. We explained to them that given our travel schedule this was not an option, and that we had a letter of invitation from the Sudanese embassy in London. This, coupled with the fact that my New Zealand passport apparently looks like a diplomatic one, was enough to get us an invitation to return an hour from then to see the consul.

We hung out in a hotel nearby where my taxi driver’s brother worked, before returning to the embassy and being allowed inside. I was shown in to see the consul, and explained all about the project as well as sharing our invitation letters and other documents. He seemed interested in our work, and said that he’d look favourably on the application, but would have to check with the ambassador. He would take our phone number and call later to let us know. So, back to the taxi, and back to the hotel where I returned to the room and managed to do a little work. Not too much, however, for before long the phone rang. It was time for our third trip of the day to the embassy!

Previous embassies had depleted our stock of passport photographs so we stopped by the side of the road and had some of me taken and printed by a man with a stool, a sheet of cloth for a backdrop, and a battery powered portable printer. I still needed photos of Sophia, however, which was to be sorted out later. Soon afterwards my driver and I arrived at the embassy and were given the forms to fill in. Unfortunately it turned out that we would indeed be needing passport photos, so a plan was put into action; Moses took a photo of Sophia, still an hour away, with his phone and emailed it to me. My driver and I then headed to an internet cafe where we downloaded the photo, and took it on a memory stick to a photo lab which touched it up and printed it out. Half an hour later we were back at the Sudanese embassy for the fourth time that day, and the applications were in! “Please come back tomorrow at 11am to collect them”. At least we could find the place blind-folded now.

That evening Moses took us to a bar and grill not far from the hotel. A couple sitting at the table next to ours heard our accents and struck up a conversation; the man, a Nigerian, worked in Leeds for T-Mobile. Apparently he grew tired of his companion, or she of him, for after a while she got up and left; he was undaunted for he picked up his phone and ten minutes later another pretty lady arrived and sat down to join him. Sophia and Moses were starving hungry having eaten nothing all day and interrogated the waitress as to how long each item took to cook, and which item would arrive on the table faster than anything else on the menu. An interesting looking goat-related appetizer was the result, with plenty of skin. I decided to wait for my main course.

We had a late start on Wednesday morning, with our first stop being the Sudan embassy to collect the visas. These were handed to us without any problems, and also free of charge! From here we continued to the headquarters of the WellBeing foundation to meet their president, and also see Dr Fasehun again. A lot of discussion was had around the composition of the “maternity packs” that the foundation was distributing to expectant mothers; they had funding for tens of thousands of these. Sophia was asked for feedback on the items included, and was able to give some very good tips on ways to save money without compromising effectiveness. One change that even I could probably have identified was the removal of a bottle of olive oil used to shine the baby’s skin after it was washed; while it no doubt looks very nice, it could not be described as a medical essential.

After stopping to collect sandwiches from a very European-style supermarket, we headed to “Area 4” to collect Lillian, a reporter from the Nigerian Guardian who would be coming with us on our hospital visit. Dr Achem had arranged for us to visit an outlying medical centre, about an hour from the city, to get an idea of how conditions varied in different locations. The drive out of the city took us past the presidential palace, which overlooked an enormous rock, of Ayer’s rock proportions. This rock was apparently sacred to the locals, and something of a symbol of Nigeria; at some point somebody had installed a gigantic “Hollywood” style sign saying, of course, “Nigeria”, but it was so dirty and decrepit that it was almost impossible to make it out.

In all honesty, the hospital was to me much like the majority of other hospitals that we had visited. The word had not gotten through that we’d been visiting, so there was no opportunity for Sophia to run a training session, and we toured the limited facilities and donated some equipment before heading back into the city. To get back onto the highway we had to drive through the market; apparently people usually didn’t try and drive down the slip road that the market had set up, so it was a case of crawling through the sea of people with the horn blaring hoping that a path would open up. Our driver became quite aggravated, but thankfully after ten minutes or so we made it through without running anyone over and were on our way back.

That evening Dr Achem arrived back from Lagos, and took us out to another “Point and kill” style restaurant. Apart from slightly different shrubbery, the garden and food were completely identical to the previous place!

Dr Achem’s assistant, Moses, took us to the airport early on Thursday morning. Sophia wanted to film an interview with him, so while they were busy with that in the lounge, I headed out to the aircraft with our handling agent Raymond. As usual, it took forever to get through the airport. First the commercial department insisted on recalculating the fees for the entire route as the value supplied by Skywatch had been nonsense; we then visited several different offices to file a flight plan, pay the airport fees and so on. When I eventually got back to the aircraft I swapped places with Sophia, who was done with her interview, and prepared the aircraft while she went to pay the final fees. Even this was not smooth, and after a long wait they re-appeared with someone from billing in tow, as apparently I had to sign the receipt as the captain. The man from billing sat for 20 minutes on the ground, calculating and writing out receipts, and we eventually managed to get under way.

As always, there were scattered cumulus clouds around and we were in and out of site of the ground as we climbed. Passing 7,000ft or so, I noticed that we were having to use rather more power tomaintain our climb speed than I was used to. Immediately checking the wheel, visible out my window, my suspicion was confirmed; despite being over central Africa, with an outside temperature of 10 degrees centigrade, we were picking up ice! A light white frosting was visible on the leading edge of the tire. We immediately tweaked our heading to keep us clear of any further clouds, ensuring that no further ice could be collected, and after a few minutes the light icing we’d picked up melted away.

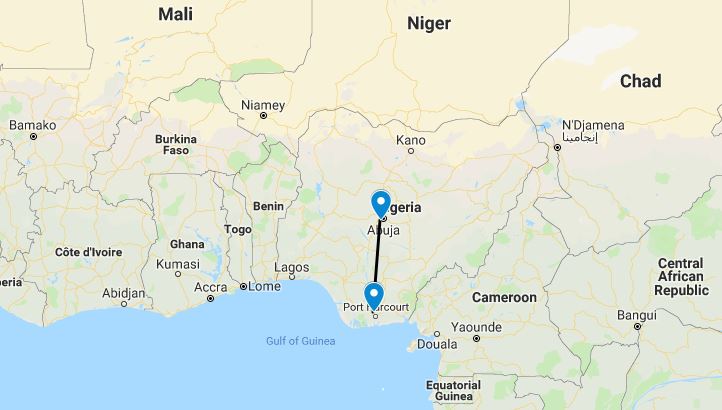

Our flight took us almost directly south, roughly alongside the Niger river. Before long we were in contact with Port Harcourt approach, who gave us clearance to descend, but vectored us out to the west of the airport with no explanation. An incoming commercial aircraft was also given delays for no obvious reason. Our new course actually took us a little away from the airport, towards the notorious Niger delta where a lot of the attacks on oil facilities occur. We could see gas flares from production facilities as we flew over, but only one or two; the majority of the area was untouched forest, or agriculture. Eventually the controller turned us back towards the airport and we flew the ILS approach over enormous palm plantations to the east of the airport.

Port Harcourt International airport was small, but seemed fairly busy. We were directed to park, as usual, right at one end of the apron to keep us out of everybody’s way. As we shut down the chief marshaler came over to intriduce himself; as with several other airports he ended up being just the helpful guy we needed and went out of his way to assist us with the formalities. A smartly suited young man from the military police came to enquire what we were up to; he threw out the usual questions as to what was our mission, did we have a permit, who was our handling agent. This last question caused something of a commotion; we didn’t have a handling agent here. We’d decided not to blow $300 on the frankly very poor service from Sky Watch, despite their emailing and text messaging me trying to persuade us that we’d need them. The military policeman was convinced that we were required to have a handling agent and after a blazing row with another member of the ground staff, the chief marshaller managed to defuse the situation. We were taken to meet the military man’s senior officer, who said that we were in no way obliged to have a handling agent and sent us on our way, wishing us a pleasant stay.

The entire terminal had been gutted for refurbishment and was covered with scaffolding. Temporary facilities had been set up in tents down one end. We were told that the work was expected to take two years or more to complete. As a domestic flight we did not have to go through immigration and soon we were outside the arrivals area, being greeted by our contact from Shell who would be hosting us for the next three days. He ushered us into a large black SUV and we set off through the traffic to the Shell Residential Area, escorted by a pick-up truck containing four heavily armed policemen. The traffic was poor, but we made reasonable progress through judicious use of the horn and occasional well-judged blocking of traffic by our escort; soon we were passing through the heavily guarded barricades at the camp and shown to our accommodation.

Our lodgings were without a doubt the best of the trip so far. We were being housed in a stand-alone villa, which contained two wings; each had a spacious bedroom, bathroom, and living room. In the centre of the villa was a shared, well equipped kitchen accessible from either living room. The apartments were very well furnished and equipped and there was even fast, reliable internet which we had been without since we left Europe! Our host, Dr Fakunde, arranged for us to meet in the restaurant a little later for dinner, with a number of his medical colleagues, to discuss the plans for the next couple of days.

The Shell restaurant was busy, with visitors from overseas as well as plenty of local families who lived in the camp. As well as the restaurant, there was a bar with live music, swimming pool, games room, hair salon, and so on; plenty to keep people amused. This was fairly essential, as one would soon get cabin fever being confined to camp with nothing to do; if you had white skin, you couldn’t safely leave the camp without an armed escort and detailed journey plan. We were, we were told, considered “HVT”s – High Value Targets.

We started early, needing to catch the bus well before 7am from the Residential Area (RA) to the Industrial Area (IA). Once again, this shuttle bus was escorted by heavily armed police in pick-up trucks. The traffic was not too bad at that time on a Friday, and after 10 minutes or so we were driving down the approach road to the IA, which was lined by police and army personnel and bunkers. We were dropped off outside one of the large office buildings, where our guide from the previous day met us and escorted us to Dr Fakunde’s office. Here I spent an hour or so with my computer connected directly to the Shell network, hoping that this would cure it of the sluggishness that had built up in it over the last few weeks. We left it chugging away applying all sorts of updates, and went to visit the Shell hospital for staff and families, inside the IA.

It was clear that Shell took the health of their employees and families very seriously indeed. The hospital was better equipped than plenty that I’ve seen in Europe or North America, packed full of well trained staff and the most advanced equipment. There was a large emergency department, with several dedicated ambulances serving it. The nurses there described how additional areas adjoining it could quickly be converted to receive mass casualties; this preparation was not in any way over the top, as they told us about one incident where tens of people had been brought in after a militant attack at a work site, most of them with serious gunshot wounds. A sobering reminder of the risks of working in such an environment.

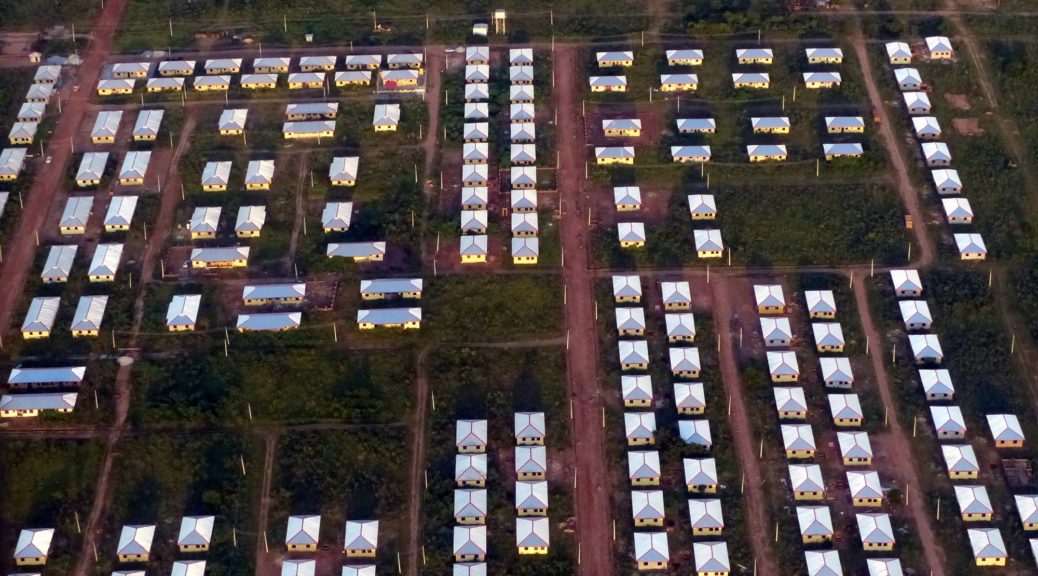

From the Shell IA, we traveled to the Obio Cottage Hospital, very close by. This facility had been working with Shell for the past three years to develop from a basic primary level centre to an impressive secondary level facility. For around $25 per year local residents could sign up with a health insurance plan that would cover any treatment at all that they might need. Pay-as-you-go treatment was also offered at apparently very affordable rates. The figures we were shown were impressive, revealing how the number of people coming for treatment over the last few years had increased many times over as word got around about the standard of care. In 2013 so far, out of 60+ HIV positive mothers, treatment at Obio had ensured that not a single baby had had the virus passed on from their mother, an incredible result. They were also proud to report that there had been no maternal deaths in 2013.

While Shell had funded some of the initial development, such as a new building, the hospital was set up to be entirely self-managing and sustaining without the need for any corporate involvement. Indeed, careful management meant that they were now making a good enough return to invest in their own equipment upgrades and further raise the standard of care. Several of the key staff we met had first come to the hospital on their volunteer program; in Nigeria most young people spend a year doing public service. Obio was such an in-demand place to volunteer that placements were limited to six months to double the opportunities. After this, some volunteers were given the chance to move to another nearby hospital where the Obio model was just beginning to be implemented, at the request of the local community.

Click here to read the next part of the story.