Round the World – Australia 3, Part 6

Although I would be staying in Manjimup for two nights, my first task the next day after a breakfast of hot chocolate and a donut still took me back to the airport. There I was meeting the president of the flying club who had offered to help me refuel, and I was planning to perform an oil change on Planey during the same visit. Both of these tasks were accomplished straightforwardly, and I returned Planey to his parking space and tied him back down.

The rest of the day was free for exploring Manjimup and the surrounding region. The area is a famous wine producing one, so the first destination was a well-reviewed local winery for lunch and, of course, some wine; I wasn’t flying after this meal so could enjoy everything the winery had to offer! The wine was accompanied by an unreasonably large cheese and fruit board; thoughts of additional courses were immediately dashed upon its appearance. When leaving I thought the man behind the reception desk looked very familiar, and asked him if he’d been working at Tall Timbers the previous night. “Not me”, he replied, “it must have been another fantastically handsome Irishman”. It had of course been him. Manjimup is a small place.

The Manjimup region has a multitude of protected national park areas around it, much of this designated in order to protect impressive old-growth forest. Not far from the winery, the Gloucester National Park surrounds the Gloucester Tree; this 58 meter tall tree has spikes driven around the trunk to form a crude ladder, and platforms at the top which used to host fire lookouts. This and a couple of other trees are now open for the public to climb; which was a huge surprise, given the very sketchy appearance of the “ladder”. Sadly the Gloucester Tree was closed today; but happily the even taller Bicentennial Tree was not too long of a drive away.

After a short stop in the nearby Pemberton to have a look at an exhibit of some old forestry equipment, it was a short trip to the Bicentennial Tree. This tree is the tallest lookout tree in the area at 75 meters (246ft) in height, and was pegged for climbing in 1988. Although it has been used as a fire lookout, its primary use has always been tourism. 165 metal spikes, hammered into the truck, serve as the ladder with a half-way platform in the middle to allow for a break. Despite the presence of a wire mesh on the sides as something of a safety measure, there is nothing to stop one from simply slipping through the very, very wide gaps between spikes and plummeting back to the ground. I nonetheless made my way, very very carefully, to the top; first up the spikes, and then up a few ladders that connected the levels of the platform structure at the top.

The views made the climb worthwhile. I sent Mitch a message to let him know I was up here doing his fire-watching job for him. He turned out to be in the air at the time on patrol, but sadly not anywhere near the tree. As I took in the view, and snapped a few photographs, the mobile phone of the young Irish chap behind me rang and he answered a video call. “Lads!” he started off, “look at the size of this fookin tree!” A braver man than I, he ended up climbing all the way down the tree while still on his video call, to the horror of his girlfriend below who was exhorting him to pay a little more attention to not falling.

That afternoon was finished off with a visit to another tree, and a couple of Manjimup’s in-town tourist attractions. The first of these was the timber arch which sits above the road entering Manjimup from the north. This was constructed before the town’s “Timber Week” in 1958, to commemorate the timber industry and act as a gateway to the Southern Forest Region.

Just down the road from the arch is the Manjimup Heritage Park. This park started off as a wildlife sanctuary in 1964. In 1977 the State Timber Museum was built on adjacent land. Since then the park has developed into something of a community hub and gives a home to the Manjimup Community Gardens, the Historical Society, the Woodturners Society, and numerous historical buildings and artifacts. Most of these are centered around the timber industry.

That evening I met up with Mitch and another flying friend of his for dinner. We wanted to try out Manjimup’s Indian restaurant; but it was full! We hadn’t anticipated that mid-week in Manjimup would be so busy. The town is not blessed with a huge number of restaurants, so we ended back at Tall Timbers again. I didn’t see my Irish friend this time.

Breakfast the following day was from the same donut shop as before, before meeting the rental car guys at the airport to return the car. On arrival at the airport a few individuals were busy pre-flighting a light aircraft while waiting for their flight instructor. A few minutes later the instructor arrived, and who should it be but the instructor from Bunbury Aero Club who had sold me fuel a couple of days before. Western Australia is geographically large, but can feel very small!

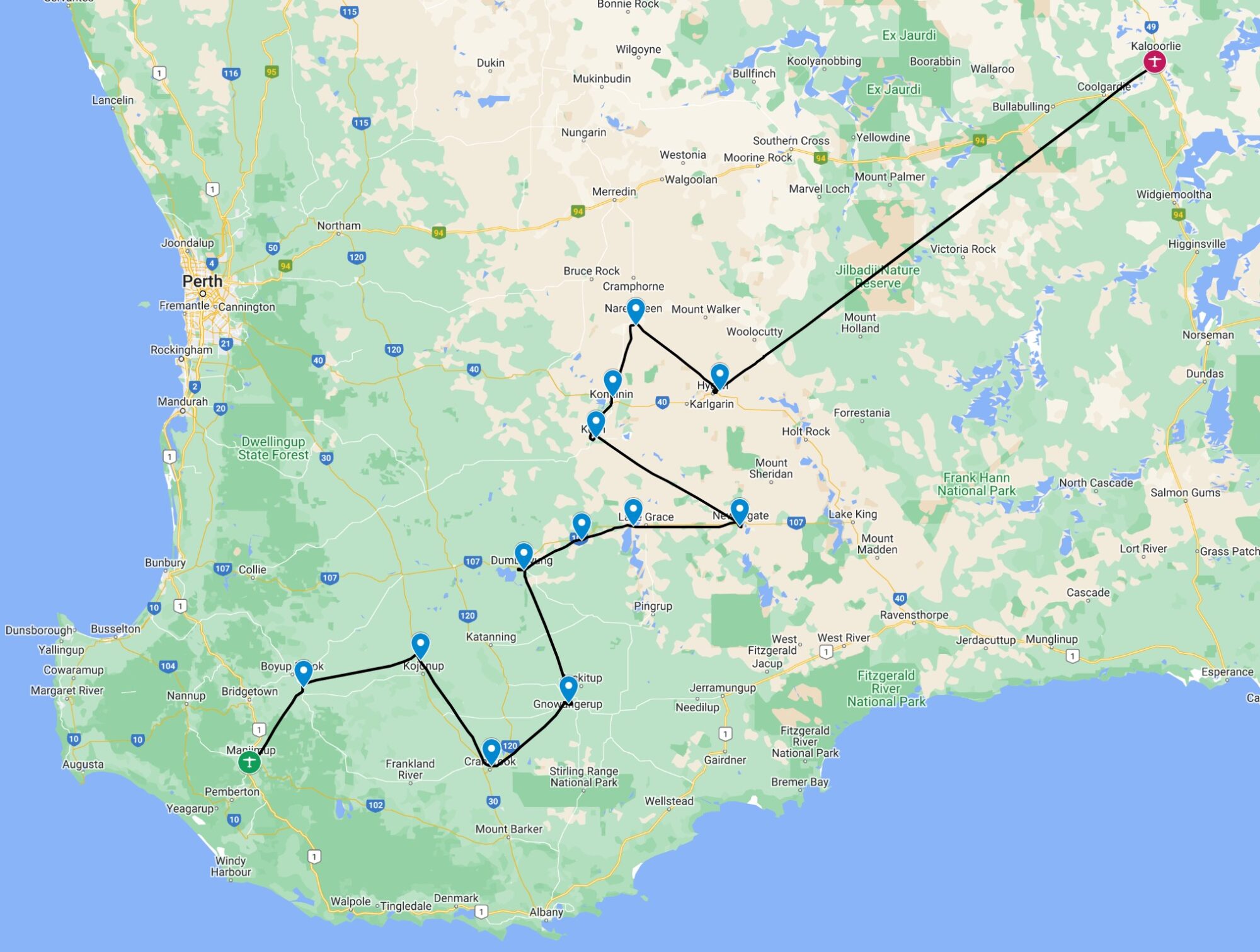

My irrational desire to land at as many airports as possible had led to my planning a slightly unusual route for the first half of the day, with brief landings at about ten strips. Lunch would be at the Wave Rock natural feature, followed by a final much longer flight northwest back into the desert.

Planey leapt into the air and we made our way across the southeast corner of Western Australia, dropping in at little country airfields along the way. Places with names like Boyup Brook, Kojonup, and Gnowangerup, as well as the less exotically named Cranbrook. I realised later that I had actually landed at this latter airport back in 2020, but it didn’t hurt to visit again and enjoy the beautiful views of the Stirling Ranges. After these brief visits I stopped for a longer break at the town of Dumbleyung. The airstrip here is within walking distance of town which offered an opportunity to buy some dinner snacks; the chosen accommodation for the night was walking distance from the airport but not from anywhere to eat! A group of other pilots had apparently had the same idea as the parking area was filled with a mixture of ultralights and autogyros. I squeezed Planey into a gap, careful not to blast any of the smaller craft with my propwash, and set off down the dirt road into town.

The walk into Dumbleyung took about 25 minutes, and only a couple of vehicles passed during that time. The center of town was made up of just a couple of blocks adjacent to the railway tracks. The supermarket was unfortunately closed as was the cafe, meaning that dinner supplies had to be sourced from the petrol station. Before stocking up, though, I took the opportunity to visit the replica of the Bluebird K7 jet boat which Donald Campbell had run on Lake Dumbleyung in December of 1964. It was on Lake Dumbleyung that Campbell set his final water speed record of more than 270mph (440 km/h). He was killed just 2 years later attempting to beat the 300mph mark on Coniston Water in the UK.

The pilots and passengers of the little microlight and autogyro fleet were hanging around outside the petrol station feeding the birds. They were out on a week-long trip flying around part of Western Australia; apparently this was an annual activity for the group of mostly retired aviators. I bought some “Pot Noodles” for dinner and spent a while chatting before taking the walk back to the airfield and heading out to visit a few more small airfields on the way to Wave Rock.

The next legs took me through Kukerin, Lake Grace, Newdegate, Kulin, Kondinin and Narembeen before arriving at Wave Rock airport. The country below looked dry and parched, and the harvest of the region’s cereal crops was in full swing. During the flight I passed through the Lake Grace wetland system; this protected wetland system includes four ephemeral lakes covering an area of more than 50 square miles, or 130 square kilometers.

Wave Rock is a natural rock formation in the shape of a wave, about 15 m (50 ft) high and around 110 m (360 ft) long. A wall lies above Wave Rock about halfway up Hyden Rock and follows the contours of the rock surface, to collect and funnel rainwater to a storage dam. These were constructed in December 1928 for the colonist settlers of East Karlgarin District.

The rock has of course become a tourist destination with a number of attractions springing up around it. This includes a caravan park, a couple of stores and cafes, and even a “wildlife park”. After lunch in the attached café I bought a ticket for this park; a white kangaroo had been visible when walking from the airport and I was keen to see more of it! The wildlife park turned out to be like no other I’d ever seen.

The first hint that this park might be unusual was the fact that one of the four model animals at the entrance was an oversized velociraptor. The second was the hand-written sign on the entry door reporting “Sorry to let you all know. The Koalas have died.” The sign went on to reassure visitors that this was as a result of old age, but that it was difficult to get replacements. Entering the park, one was greeted by a cage of exotic birds which on further investigation proved to be plastic.

The park did feature some live animals; Kangaroos, Emus, Alpacas, and a variety of birds and reptiles among others. The real animals were almost outnumbered by plastic ones from areas rather further afield; elephants, lions, and a variety of dinosaurs. Bemused, I left the park and decided to skip the “lace museum” and “toy soldier museum” that were on offer from the same establishment.

Wave Rock itself was a short walk further on, the other side of the road and through a caravan park. There’s not much to say about it; it’s a big rock, and it looks like a wave. If you’re passing through then I’d say it’s worth stopping to check it out. After snapping a few photographs I walked back past the airport and along a short access road to the Wave Rock Resort, and the Lake Magic Swimming Pond.

Lake Magic is a naturally occurring salt lake with gypsum minerals at its base and a sandy, circular beach surrounding it. The high concentration of minerals makes the water denser than usual and, much like in the Dead Sea, this makes swimming in it an unusual experience with swimmers floating higher in the water than they’re used to. The Wave Rock Resort has gentrified a small pool next to the main lake that shares the same water, surrounding it with changing cabins and lining the edge with rock and access stairs. After a bit of a float I headed back to Planey for the final flight of the day.

This final flight would be a 1.5 hour, 200 mile leg back towards Australia’s hot dry center and Kalgoorlie. The city was established in 1893 during the Western Australian gold rushes and today has a population of just under 30,000. Its environment is dominated by the nearby “Super Pit” gold mine which until 2016 was the country’s largest open-cut gold mine. The pit is oblong, and is approximately 3.5 kilometres long, 1.5 kilometres wide and over 600 metres deep. Today mining employs about one quarter of Kalgoorlie’s population and accounts for a greater proportion of its economy.

The main GA parking area at Kalgoorlie is a long walk from accommodation but a smaller apron sits on the other side of the airport and is more conveniently situated. I had phoned the airport authority in advance and received permission to park there, cutting the walking by at least 20 minutes. Tie-downs were available in the corner so I secured Planey there for the night. There was no exit immediately visible but a fire gate nearby looked like it would be climbable. There was a relatively busy road the other side of the fence but surely nobody would call the police because of somebody breaking out of an airport?

That night’s accommodation was at the nearby Discovery Parks campground which offered cabins as well as camping spots. The pot noodles proved to be insufficient and Dominos pizza came to the rescue.

The next morning I awoke before dawn for a long day of flying and walked back along the road to the airport. Deciding that climbing over a fence into an airport would look much more suspicions than climbing out of one, I opted instead to walk the long way around to the other side of the apron where I came across a pedestrian door hidden down the side of a hangar. Airport operations had given me the code earlier so I was able to enter legitimately and prep Planey for flight.

It was too early in the day for Air Traffic Control to be on duty. I started up and taxied out, paying particular attention to the traffic frequency on the radio as the two ends of the runway are invisible from each other. Right as the sun started to peek over the horizon I pushed in the throttle and leapt into the air, climbing out over the enormous “Super Pit” gold mine.

The first flight was a 450 mile leg across towards the desert towards the center of Australia. Rain showers and storms were visible off to both sides as I cruised along on autopilot in the smooth morning air, and occasionally diverting left or right to keep clear of the weather. My first stop was the community of Warburton. This community was set up as an Aboriginal mission in 1934 and is named after Peter Warburton, the first European to cross the Great Sandy Desert. Today it has a population of a little under 600. The town offers a rare resupply point in the central desert and the Warburton Roadhouse offers lodging, food, and fuel as well as avgas. For once though I didn’t need fuel; I would be filling up at the next stop.

A large storm had clearly recently passed through, as evidenced by the large puddles on the apron. After a short stop I fired the engine back up and set off northeast again towards Warakurna, the final stop in Western Australia. This community is similar to Warburton but smaller, with a population of less than 300. It was incorporated in 1976 due to the need for a new community to alleviate overcrowding at Docker River and Warburton.

The location was, and remains, the site of the Giles Weather Station. Named after the first European explorer to pass through the area, this station is staffed by a 3-person crew who work 6-month rotations. Duties include the daily release of weather balloons to take atmospheric readings. It was established in the mid-1950s to provide weather forecasts in support of nuclear weapons testing in the area, and is the only manned weather station within an area of almost one million square miles.

I had called the roadhouse at Warakurna in advance to confirm availability of fuel, and called again on arrival. A few minutes later a battered white SUV hove into view with Nathaniel, the son of the roadhouse manager, behind the wheel. He squeezed under the fence and bounded over to say hello. He chatted away as he unlocked the fuel pump and prepared to dispense avgas, talking about his previous working experience in a variety of remote parts of Australia. Suddenly he presented a question; “How old would you say I am?” I’m not very good at judging things like that; he looked young, but it sounded like he’d done a fair few things with his life already, so I ventured a guess. “No older than 30” I suggested; he was a little put out at this, turning out to be only 20.

He soon bounced back from this. “Do you want to hear some Dad jokes?” he asked. Obviously the answer was yes, and he dove into a variety of increasingly bawdy quips and one-liners. “That tree over there is a dog tree – you can tell by its bark!” and “Did you hear about the cross-eyed circumciser? He got the sack!” being two of my favourites.

Once Planey was fueled up Nathaniel gave a lift to the roadhouse to stock up on a few snacks and pay for the fuel. This done he drove me back and I set out again to the northeast, back into the Northern Territory.

I stopped briefly at Docker River before continuing towards the famous Ayers Rock (now more commonly known as Uluru). While I had visited this iconic landmark back in 2019 in the rental 206 I had not had the chance to fly over in Planey, and the chance to see it again was too tempting to resist. The usual scenic flight route begins and ends at Ayers Rock airport but I was coming in from the other direction, out of the west past the other dramatic rock formations in the area known as the Olgas. I tuned in to the common traffic frequency for the area and listened in for a while to get an idea of traffic before announcing my intentions; there were just two other aircraft in the scenic pattern, and I’d be able to keep well clear of both. A commercial jet was also on the way into Ayers Rock airport from the north but would be well out of the way before I was departing in that direction.

After a couple of scenic passes by the rock I turned north, climbing clear of the traffic pattern. The incoming commercial jet was already below my altitude so there was no conflicting traffic to worry about. This next leg took a little over an hour, as far as the small airstrip at the community of Haasts Bluff. This small Aboriginal community of roughly 200 people is named after the nearby rock outcrop, given this name in 1872 by the explorer Ernest Giles after the German-born New Zealand geologist Julius von Haast.

The stop at Haasts Bluff was brief, and before long I was lifting off again for the penultimate flight of the day. This took me eastwards across the Northern Territory, passing north of Alice Springs and touching down at the Gemtree Caravan Park which is equipped with its own dirt strip. As well as just being an interesting new place to land, they had a small café and shop which offered an opportunity to restock a few items.

The later section of this flight took me along Highway 12, a partially tarmacked and partially dirt road connecting the Northern Territory with Queensland. A “ute” could be seen down below, pulling a large caravan eastwards. I landed to the south, skimming over the highway as the caravan pulled in to the entrance to Gemtree.

I taxied back and parked up on the strip itself; no safe parking area seemed to be available, and I didn’t want to inadvertently direct the nosewheel into an animal burrow or similar. As I shut down an old Landcruiser pulled up, driven by one of the park owners. He was in a hurry to get back and check in the new arrival, and gave me a lift to the office/store. There wasn’t much going on; apart from the owner and new guests, the only other person around was an old chap sitting in the shade relaxing.

After a quick snack the owner drove me back to the strip, peppering me with questions about what I thought of the runway. He was debating expanding the park to include parking and fuel for trucks, and a mobile phone mast, and was interested in a pilots’ view of how these new facilities might affect aerial activity. This is not my area of expertise but I gave what advice I could and was soon on my way.

The final flight of the day was a short hop south across the rugged ridges and valleys of Australia’s arid center. The night would be spent at the Ross River Resort. There is no mobile phone service at the strip so the manager had asked me to perform a low fly-by of the main resort buildings prior to landing, so that they’d know it was time to make the ten minute drive to pick me up. Coming in from the north, I performed the fly-by as requested (keeping a safe distance from the buildings of course!) and lined up on the strip for landing.

Dirt strips in Australia are very different to dirt strips I’ve flown to in many other countries. In the UK, New Zealand, and the US these strips are often short and challenging; in Australia, the sheer amount of space means that dirt strips in many parts of the country can still be long, wide, and often maintained to a standard that even a jet could operate. Ross River was no exception and I used just a fraction of the 1000+ meter runway before parking up to one side of the runway and securing Planey for the night.

Within a few minutes ones of the managers, Lee, had arrived in the seemingly mandatory Landcruiser. She provided a lift back to the resort, telling stories along the way of the wild donkeys that roamed the area in a herd. Apparently the risk of their assaulting Planey overnight was low.

These days the resort is managed by Lee and Graeme, who have been on site since 2012. After dropping off bags at the room Graeme offered up a tour of the homestead and spoke about some of the long history of the site.

It is thought that Alfred Tabe, the foreman at the nearby Arltunga Gold town built the homestead in 1898. By 1901 the homestead had changed hands and was being used to supply fresh vegetables to the miners. In 1908 the property was sold again, this time to Lewis Bloomfield. Bloomfield was an expert horseman and so began the homesteads’ long history of providing high quality horses to customers across Australia such as mines and the military. In 1944 Bloomfield died and just over a decade later the homestead, now in a state of disrepair, was sold to the Green brothers who spent the next seven years getting things back in order before opening up as a tourist resort. Cars had become popular, ending the era of the horse, and at just 15,000 acres (tiny by Australian standards) the station was too small to convert to cattle duty.

The station did have considerable reserves of timber, and supplied 30,000 sleepers for the construction of the Ghan railway. Tourism boomed and before long the resort was the top recreational destination in the NT, with airlines landing aircraft as large as Fokker Friendships on the strip. When the Ghan was abandoned in the 1980s the resort owners “liberated” a multitude of sleepers and even an entire bridge, using the materials to extend the homestead including construction of a large dining area.

Graeme finished off the trip with an introduction to a local resident; a python who was asleep in a fireplace on the front porch. I killed an hour or so before the evening meal exploring the area, including the local “auto museum” – a selection of historic cars almost rusted away into the dirt. Finishing up the evneing, Lee served up a fantastic Moroccan chicken for dinner. I finished off the evening with a short walk away from the resort buildings in the darkness to enjoy the clear night sky, laying on the asphalt of the road and gazing at the stars.

The nights’ sleep was interrupted only by the chase and capture of an enormous cockroach.

Click here to read the next part of the story.