Round the World – Australia 3, Part 5

By the next morning the rain had ceased. The hotel laid on the shuttle bus back to the airport. Driving across the river, the impact of the previous day’s rain was already obvious; sand bars which had had swimmers lounging on them the day before were now entirely submerged, and the speed of the river had picked up remarkably. It would not be long, just a matter of weeks, before this bridge was washed away entirely.

A pilot was pre-flighting one of the Robinson helicopters out at the airport, which was fortunate because there was no obvious way to get back in through the gate unless someone was there to open it from the inside.

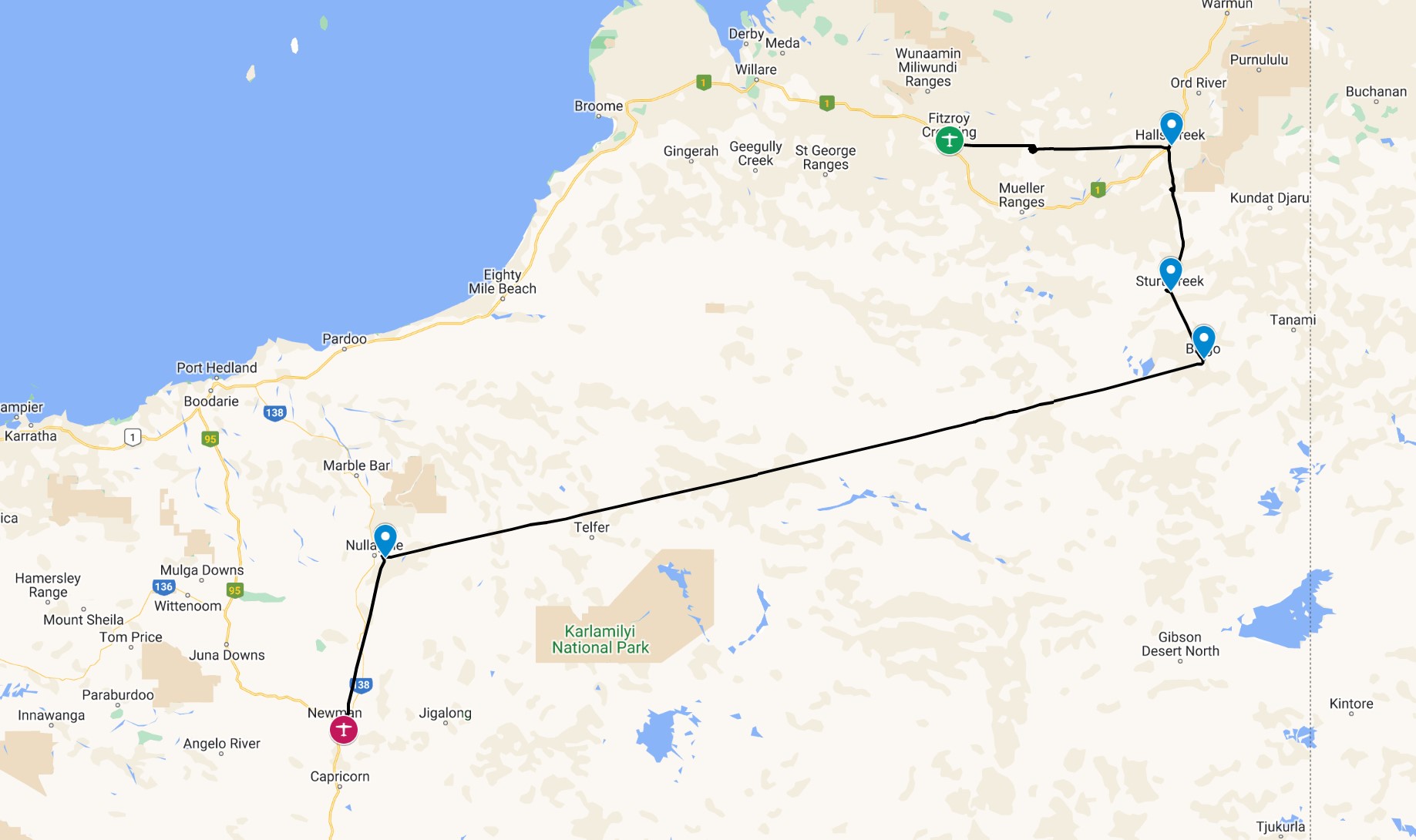

The first flight leg was east to the town of Hall’s Creek, for fuel. I had previously landed here, also for fuel, back in 2019 on my first arrival to Australia. On this occasion I wanted to head in this direction to see the Wolfe Creek Crater, and Halls Creek was the only fuel around.

The route loosely followed the course of the Margaret river. About half way, a dramatic sight came into view below; a flash flood was making its way down the Margaret. I’d seen plenty of videos of such a phenomenon in the past, but had never laid eyes on an example in real life. These floods are generated when a heavy rain falls in a dry area, and the run-off is all funneled into the river in one go. A previously dry riverbed is suddenly assaulted by a wall of water and debris making its way downstream. This is a reason to be very careful in dry riverbeds; the rain that causes a flood can occur entirely out of sight upstream, and the first warning you get of the flood is the sound and sight of the water bearing down on you.

I couldn’t miss the opportunity to see this, and descended to circle the flood-front and get better views. A couple of cattle could be seen fleeing from the riverbed as the water approached, both making it to safety in plenty of time. The impact on the river was dramatic; the flood-front separated a mostly dry riverbed with the occasional still pool from a turbulent, debris-laden torrent of water that filled the channel from bank to bank. After my fill of flood photos, I climbed Planey back to a comfortable level and continued on the way to Halls Creek.

The fueler at Halls Creek had changed out since I was last here. The new guy had not been around long, but was able to figure out the Avgas sales process without too much difficulty; this was another Air BP location, where buying fuel as a non-cardholder was not straightforward. Upon learning that the next leg would be to Wolfe Creek Crater, he had some helpful advice to offer: “Don’t land there – you’ll get murdered!”

He was referring, of course, to the 2005 Australian horror movie “Wolf Creek”, where three backpackers have their car break down at the crater and end up being creatively murdered by a deranged local. If reading this has caused you any “spoilers” for the plot of the movie then sorry, but it was released 18 years ago, so you really should have seen it by now.

Not far out of Halls Creek, I spied a victim of the recent rains. The Tanami highway runs from Halls Creek, southwest to Alice Springs. The old mid-point roadhouse has closed down, so there is now a 900km stretch with no fuel or services at all. 80% of the road’s more than 1,000km (640 mile) length is dirt or gravel, and a triple road-train had become hopelessly bogged on the road down below me. Time, perhaps, for a bit of an Australian language lesson; a road-train is a huge multi-trailer articulated truck, used for hauling large quantities of cargo across Australia’s vast distances. Being “bogged” is to be stuck in the mud. This road train had clearly become bogged and unhooked two of its trailers to try and make it out. It had progressed a few hundred meters further before coming to rest entirely. There wasn’t much I could do for him from up here, so after circling once I continued south.

Wolfe Creek is known as the second most “obvious” crater on earth, and is relatively young at less than 120,000 years old. It was not known to western science until being spotted during an aerial survey in 1947. It is thought to have been formed by a 15m (50ft) diameter asteroid, weighing about 17,000 tonnes. It was well worth the detour out to see it, sitting strikingly in the middle of a vast flat landscape. I didn’t land, and thus avoided being murdered, continuing on my way south to land at a couple of local strips before the long flight across the Great Sandy Desert.

A quick landing at Billiluna was followed by a slightly longer stop at Balgo. The next leg would be a several-hour flight, so this was a nice opportunity to stretch the legs and enjoy a snack before setting out. The Balgo Hill Airport serves the community of Balgo, which has a population of a little over 400, and was established by German missionaries in 1939. Its population are drawn from a number of local aboriginal groups, speaking a total of eight different languages. I didn’t see any of them, as I was soon roaring down the large, smooth runway and striking out into the Great Sandy Desert.

The Great Sandy Desert is the second largest desert in Australia after the Great Victoria Desert, at nearly 300,000 square kilometers, more than 100,000 square miles. The main populations consist of Aboriginal Australian communities (the Martu people in the west, and the Pintupi people in the east) and mining centres. The main terrain of the desert is the “erg”, also known as a dune field; some of these dunes stretched out seemingly endlessly, marching away across the horizon. Splashes of green were visible here and there from the recent rains, but mostly the landscape was sparse.

Low cloud hung around west of the airport, and the first part of the flight was spent up above it. After an hour or so it gradually broke up and disappeared, and the desert could be enjoyed in its full splendour. Towards the western edge of the desert a number of mines came into view; Telfer, Nifty, and Woodie Woodie are some of the big ones, producing Gold & Silver, Copper and Manganese respectively. They have their own airstrips for workers to fly in and out on their shifts, living on site while on-shift, but these airstrips don’t tend to welcome itinerant visitors unless they have a good reason! Not much further on is the town, and airstrip, of Nullagine which was to be the day’s penultimate stop.

Nullagine is an old gold-rush town in the Pilbara region. Gold was discovered in the area in 1886, and the town was officially declared in 1899. In the early 1900s the town population reached as high as 3,000; as well as gold, diamonds and a variety of other gemstones were discovered. In recent years iron ore has been discovered in the region and may lead to a resurgence in the town’s fortunes; for now, thew population sits below 200. After a short stop to stretch the legs after the desert crossing, I departed south towards Newman.

Newman is one of the largest towns in the region, with a population of more than 6,000. It started life as a company town, constructed by a BHP subsidiary in 1966 to support the development of iron ore deposits at Mt Whaleback. The company also constructed a private railway all the way north to Port Hedland; in 2001 a 7.35km (4.57 mile) long train, consisting of 682 ore cars and 8 locomotives, set a record for the longest train in history. The airport is large and modern, serving a huge number of “fly-in, fly-out” workers who work in the mines around the region.

I had booked a room at a nearby accommodation camp, “Oasis”. It was about a 30 minute walk from the airport but it was mid-afternoon and hot, so after refueling Planey I called a taxi and waited as the camp had let me know they had nobody available for a collection run. After 20 minutes, I began to suspect that nobody was coming; luckily, a car pulled up with “Oasis” branded across it. The occupants had come to collect three important visitors but it turned out that they had missed their flight and hadn’t arrived, so a lift was provided back to the camp, with a brief delay to figure out how to get out of the carpark as the barrier had stopped working. About an hour later, I received a text message telling me that my taxi was arriving at the airport.

The accommodation camp felt very comfortable and familiar, having spent a few years at a very similar (but rather higher security) camp in the Iraqi desert. A few plusher rooms were set up to cater for the occasional tourist. Dinner was buffet-style in the large dining room, with about a 20:1 male to female ratio!

The next morning, once again no lift was available to get to the airport, so it was time to get walking. It was at least cooler than the previous afternoon. Plenty of traffic went past, but only one vehicle looked like it was stopping to offer a lift – unfortunately it sped off again a few moments later. The walk was not too onerous though, and soon I was easing Planey off of the runway and heading west.

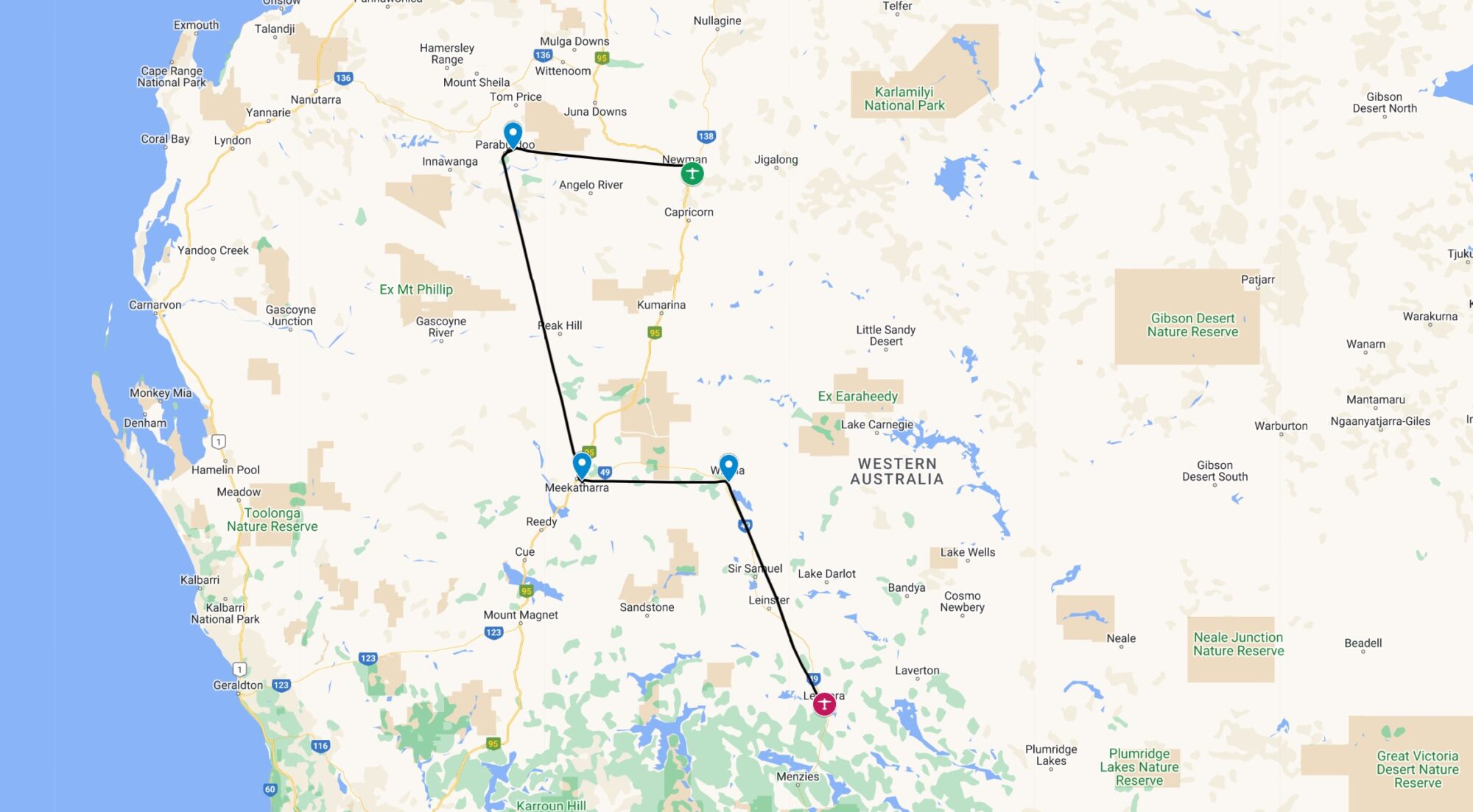

Today’s flights would thread through the desert, stopping at a few regional airfields along the way. The first of these was Paraburdoo. Like many towns in the area, it was developed by a mining company to support their nearby iron ore operations, being gazetted as a town in 1972. As with Newman, the airport primarily caters to “fly-in, fly-out” workers. As I neared the airport a Qantas flight announced their imminent departure on the radio, so I extended my downwind leg to give them plenty of time to take off.

On arrival I enquired with a couple of car hire desks about the possibility of renting a car for an hour to go and visit the nearby Resilience sculpture. Made using iron from the nearby mine, the sculpture was created by WA sculptor Alex Micke in collaboration with the local community and weighs over 9 tonnes. Sadly, no car could be had for a reasonable price and so I resolved to simply fly over the sculpture instead.

Departure from Paraburdoo led me over the nearby mines, offering great views of the operations below. These local mines, operated by Rio Tinto, can produce up to 20 millions tonnes of iron ore per year which is then transported by rail to Dampier for export.

I continued through the desert, stopping off in Meekathara and Wiluna. Both towns are small, and support the local mining industries which exploit iron, gold, lead and uranium reserves. They also provide services to the limited agricultural activities which take place in the region, although the countryside is not appropriate for much of this with over-grazing and other exploitation having damaged the landscape in previous years.

Tonight’s stop was Leonora, near the southern end of the deserts. Predictably, this is a mining town; nearby mines extract gold and nickel. The town is named after the nearby Mount Leonora which itself was named after the niece of John Forrest, the first European explore to visit the region back in 1869. The airport was quiet and landing was straightforward; the parking area was empty so I had my pick of spots. Storms were around again, so I made sure to secure the cabin cover nice and tightly.

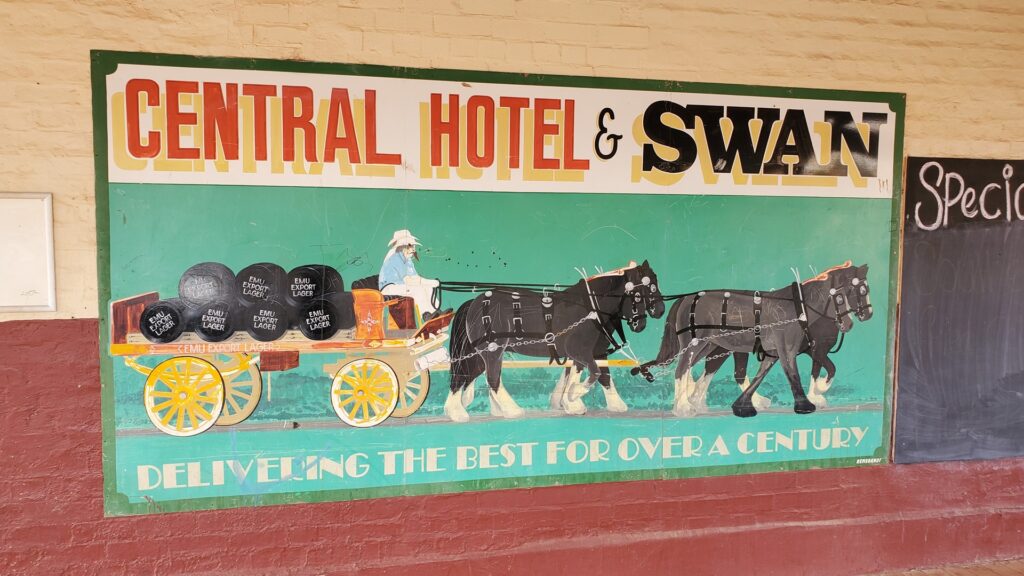

An airport employee was just leaving, and offered a ride into town. It was only a 20 minute walk, but this was gratefully accepted anyway. There are not many places to stay in Leonora; one of these is the Central Hotel; a pub with a few porta-cabin motel rooms out the back. It was clean and comfortable though. Most of the rooms were occupied by workers, although the motel was nowhere near full. The town was small, and it took just a few minutes to walk up the main street and back. That was followed by a drink in the pub, and a rest before dinner; in the same pub, of course.

It was an early start the next day, with a long day of flying planned all the way down to the very south-western tip of Australia. My aim was to visit a handful of airstrips around the coastline of this region. One of the hotel staff was kind enough to provide a lift back to the airport, and Planey was soon pre-flighted and ready to go.

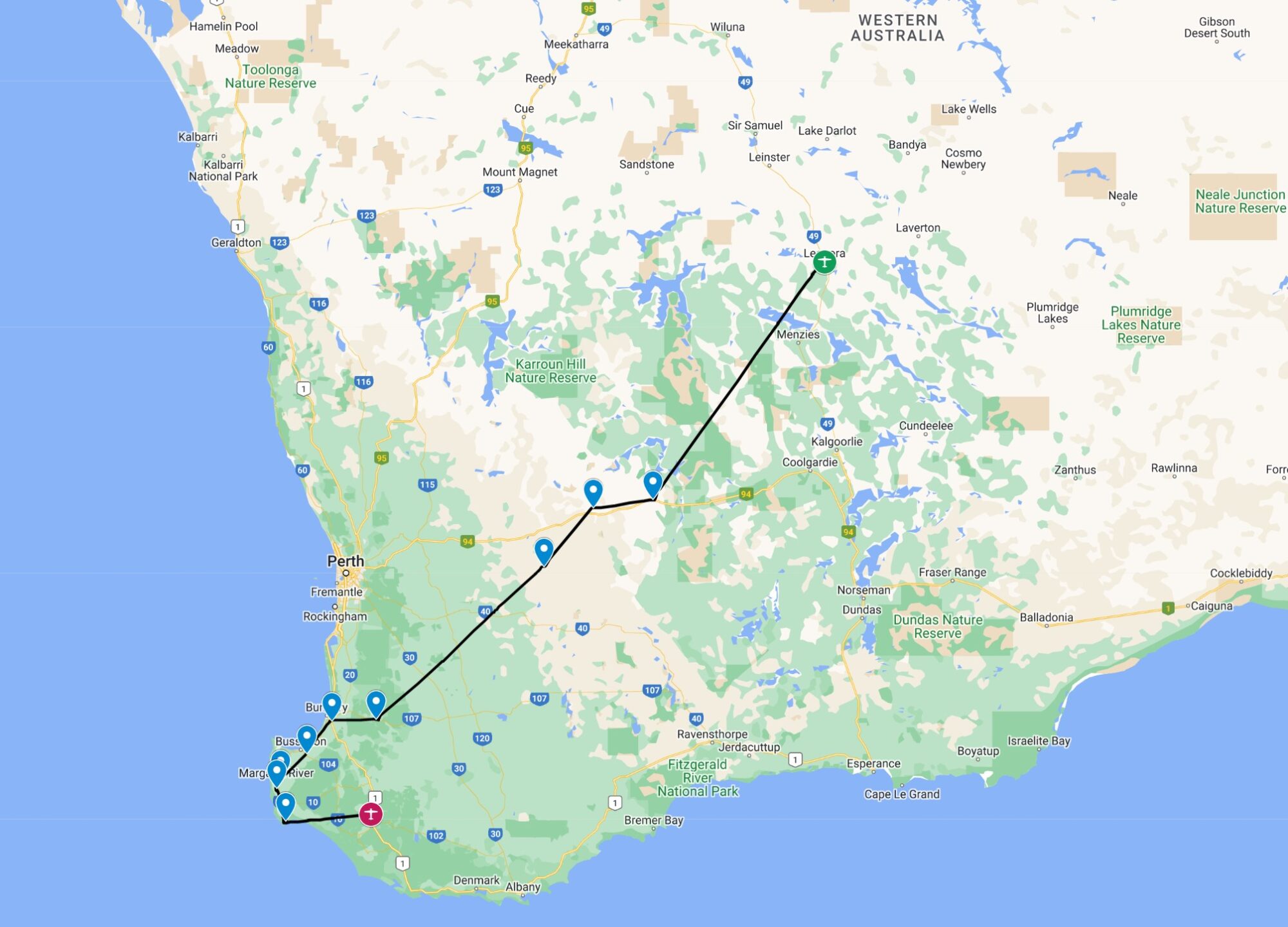

I taxied out a little ahead of a regional jet, most of the passengers of which appeared to be on shift change from the mines. Take-off saw us passing over abandoned mine workings, some of which were now flooded and had become man-made lakes. The first leg of the day’s flying was around an hour, and saw the terrain down below change from sparse desert, to the beginnings of fertile agricultural land. The southwest of Australia is known for its productive farmland and, nearer the coast, high quality vineyards.

This farmland has historically been protected by a number of rabbit-proof fences, first built in the early 1900s, in an attempt to prevent the spread of rabbits from the east. It was one of these fences which we flew over shortly before the end of this first leg. The introduction of rabbits into Australia is widely credited to (or, more accurately, blamed upon) Thomas Austin, an Englishman who released 24 breeding rabbits onto his estate in October of 1859. In an early example of somebody shrugging their shoulders and proclaiming “What could possibly go wrong?”, Austin noted that “The introduction of a few rabbits could do little harm and might provide a touch of home, in addition to a spot of hunting.”

Mild winters allowed the rabbits to do what rabbits do best not just during the spring and summer, but all year round. Within 10 years, 2 million rabbits a year were being killed, with no noticeable impact on the population. A genetic study in 2022 confirmed that all rabbits in Australia are descended from Austin’s 24 rabbits. Three rabbit fences were constructed; the first was the longest and ran from coast to coast, north to south, with a total length of 1,139-mile (1,833 km). It was unsuccessful at keeping the rabbits out.

The first stop was Southern Cross, a regional town of about 700 residents. Southern Cross is nestled firmly in the agricultural region and is surrounded by crop fields, primarily wheat and other cereal crops. Named after the Southern Cross constellation, the town’s streets are named after other constellations and stars. The town is one of many which were built along the Goldfields Water Supply Scheme pipeline, which was constructed at the end of the 1800s to take water from the Perth region inland to the gold mining towns, as far as Kalgoorlie. The pipeline still operates today; with many updates and upgrades, of course!

From Southern Cross I pressed on to the south west, with landings at the small strips of Westonia and Bruce Rock. Bruce Rock was a longer stop to stretch the legs; the airstrip was deserted, with just a little parking area and a couple of slightly decrepit hangars. Soon, though, it was time to get going again; there was a lunch appointment to make it to!

Not long after leaving Bruce Rock, the terrain down below started to change from wide flat fields to more hilly, forested country, including a number of protected state forests. Scattered cloud thickened up over the hills, but started to break up again as we neared the coast and the sea finally hove into view. This was a welcome sight after days of sparse, red desert; the countryside around the coast was lush and green. I pointed Planey’s nose down towards the airport at Bunbury, landing to the west and taxiing to the fuel pumps.

There was just one individual on duty at the flying club, an instructor, and he walked over to deliver the card for the fuel bowser. I topped up the tanks and headed in to pay, picking up a Bunbury Aero Club shirt as a souvenir. There wasn’t time to hang around too long though, as I wanted to visit a couple more airstrips before lunch.

The route took me south along the coastline of this south-western-most part of Australia, the sun beating down on beautiful southern beaches. After brief stops at Busselton and Margaret River (the latter of which requires permission from the operator in advance) I approached the grass strip at the Leeuwin Estate winery.

The winery at Leeuwin Estate was established in 1973, and produces about 60,000 cases of wine a year from the 121 acres of vineyards surrounding it. As well as a tasting room, the winery features a renowned restaurant which has at times been awarded such distinctions as “Regional Restaurant of the Year”. Most importantly, there is a grass airstrip on the estate just a short walk from the restaurant and tasting room which is open to visiting pilots if they have a restaurant reservation. I was fortunate that they had been able to offer a reservation on short notice, confirming just that morning.

The route to the restaurant was not clear, but a bit of wandering eventually led to the back door. Out the front of the restaurant was a beautiful lawn, with two commercial helicopters parked on it; they were from a tourism company that offered trips such as lunch at a winery! This was even more fancy than coming in by plane. The restaurant was full, and despite not being able to enjoy any of the wine (drinking and flying is frowned upon), the meal itself was well worth the visit.

The afternoon was starting to draw on, and it was soon time to depart. Before arriving at my night stop, there was still time for one last stop, and this was to be the town of Augusta. This is the closest town to Cape Leeuwin, the furthest southwest corner of the Australian continent.

The town is small, with a population of about 1,100 and was founded in 1830 as a sub-colony of the Swan River Colony which had been established at what is now the city of Perth. These days, the relatively cool climate of the region makes the town popular for retirement and tourism. The airstrip is surprisingly densely developed for such a small town, with hangars squeezed into every apparent available spot. I set out to walk down to the coast and was surprised by how small and seemingly hidden the access road was. It was a little under 30 minutes walk to the waterfront, through a quiet residential area, and it was certainly clear why people would choose to retire or holiday here.

I had an appointment to collect a hire car, so sadly couldn’t spend too long hanging around at Augusta. The day’s destination was Manjimup, where I had been invited to visit Mitch, a pilot friend who was in the area flying fire patrol for the season. The countryside surrounding this town was beautiful, and I admired it as I flew in; the area was dotted with vineyards and other horticultural enterprises, all of whom seemed to have created little lakes and ponds on their property; presumably to support irrigation through dry periods.

The airport was deserted, but I had been given instructions on where to park, so secured Planey ready for a two night stay. Moments later the hire car turned up, and I headed to the motel. Dinner that night was at “Tall Timbers”, a local restaurant and wine tasting room.

Click here to read the next part of the story.