Africa – Kenya to Tanzania

I took a taxi to the Aero Club arriving at around 0900, and bumped straight into our engineer Rick. We first walked over to Phoenix to find out exactly where they wanted us to bring the aircraft; being a Sunday not many people were around, but Rick had spoken to one of the facility’s managers beforehand and arranged for us to work there on the weekend. We were directed to take the aircraft to the closer hangar, and once we arrived back with the airplane the standby engineers descended upon us keen to help out and learn about the unusual diesel engine. On a normal day, they told us, they’d simply have to hang around doing nothing so the chance to help out on the diesel was apparently a welcome change!

With Rick, myself, and some help from the resident engineers the aircraft inspection was completed in record time. If the stores had been open to pick up the required replacement brake pad and lightbulbs, we’d have been entirely finished in less than a day. The work was very thorough; 30+ inspection panels all across the aircraft were opened up; glow-plugs, fuel injectors, and filters throughout the engine were replaced, the cylinder compressions were checked, and the oil changed along with a multitude of other tasks. With the work almost complete, the aircraft was put to bed for the night and Rick and I retired to the Intercontinental for another excellent curry.

I made it out to the airport a little later than the day before, and Rick was already hard at work at Phoenix. The lightning pace of the previous day had ground to a halt. Phoenix’s chief engineer had turned up, and taken great umbrage at the fact we would dare to work at the facility on a Sunday. The fact that it had been organised with one of the managers of the company seemed to be of no consequence to him, and he’d given Rick a very hard time. The engineers assisting us this time were working at a glacial pace; the intervention of the boss had definitely not helped. When I arrived he came and had a go at me as well, and stalked off without replying when I pointed out that we could hardly be help responsible for any deficiencies in their internal communications. We didn’t see him again.

Mid-morning, a large group of middle-aged men wandered along the apron, dressed in high-vis vests. With them was a representative from the airport authority. They were all clutching notebooks, and it became clear that this was a group of hardcore plane-spotters. They were going from aircraft to aircraft, scribbling down the registration numbers, and had even organised to come into the Phoenix hangars to ensure they noted down every aircraft that was undergoing maintenance as well. They were perfectly harmless, but it was odd to see that they were entirely uninterested in the aircraft themselves; they simply wanted to collect registration numbers for their notebooks.

Late that morning we tested the alternator and, as I had guessed, found it to be defective. Instead of the required 28 volts, it was producing only 23 or so. All the evidence pointed to an alternator that had been provided defective from the manufacturer, and had been slowly deteriorating. In a flurry of activity it was arranged that a new part would be sent out. A few options were investigated, including carrying the part on a Phoenix jet that was visiting Frankfurt that week, but it was eventually decided that the part would be carried out by a friend of the owner who happened to be flying to Nairobi. It would arrive early on Thursday morning, by which time our engineer would have departed, but thankfully another qualified engineer was located. He was arriving into Nairobi on Wednesday, quite by chance, and staying for some months; perfect! We moved the aircraft out of the Phoenix facility and down the airport to the hangar of the Mission Aviation Fellowship (MAF) whose engineer would be replacing the part for us.

Rick and I carried out a few last tasks on the aircraft, including removing the old alternator to be returned to the owner. This done, he departed for the airport and his flight home to Holland. That afternoon I caught up on some work, and also arranged with a local flying school to take one of the Cessna 172s for a short trip the following day; the plan was to go with their chief instructor and practice some dirt strip flying south of the city. It would make a welcome change from hanging around on the ground! The families had departed this day; my parents to Cape Town, and Sophia’s family to elsewhere in Kenya for a week’s safari. It felt quite strange to be just the two of us again.

Sophia, having had enough of hanging around Nairobi, departed on a commercial flight to Mombasa. She was planning to visit some friends who lived north of there on the coast, and also do some medical work in Mombasa itself. Left to my own devices, a flight was exactly what I needed, and just after lunch the chief pilot at Pegasus flight school came to find me; he was ready early, so did I fancy going now? We pre-flighted one of the school’s Cessna 172s and taxied to runway 14, the usual departure runway. It was quite a relief to have someone else doing the radio for me; the frequency was as busy as ever and just to make things more difficult the radios and intercom in this aircraft were remarkably distorted and hard to make out.

We flew south at 6,200ft, climbing to 6,500ft to just clear a small ridge before the ground dropped away dramatically into the Great Rift Valley. The floor of the valley was fairly desolate, being even hotter and dryer than the plains where Nairobi sits. One large farm could be seen; my companion told me that it was fairly new, and was not expected to last long. Our destination, Malingi, was a dirt strip sitting next to a large salt lake and serving the salt processing factory and small community that surrounded it.

A low pass cleared the herd of goats off of the runway, and we flew a circuit back around to land. Having a lot of experience with short strips and grass strips, as well as some very strange tarmaced strips in the US, the landings here were not challenging; the strip was fairly long and straight with nice clear approaches. It was good fun to land on dirt though, as a break from the usual. We flew three circuits, my first being a little rusty after some time not flying a 172, before beginning the long slow climb back to Wilson; we had to climb 2,000ft before we even made it back to Wilson’s airport elevation.

Coming back into Wilson the traffic was even busier than on previous occasions. I was glad to have a local expert with me to handle the radio and point out the usual visual reporting points. We slotted into the stream of Cessna Caravans and were asked to expedite our approach; the reason for this became very clear as we were pulling off of the runway and looked back to see a Caravan pass just behind us having landed while we were still on the runway!

That evening I hung out in the lounge at the Aero Club, before being invited to join a group of regulars at the bar. There were several pilots from various operators at Wilson, a lady who worked in the flight ops at Phoenix, and the son of one pilot who’d just returned from working on a farm in Ethiopia. The evening passed quickly, with plenty of stories of exploits in Africa, prominent among them being the attack of a Lemur in a hotel in the Comoros Islands. It was well past midnight before we all retired.

Our alternator arrived as scheduled, landing at 6:30am, and was delivered to the Aero Club in a taxi. I wasted no time in heading to MAF and locating our engineer, Keith, who’d be returning the aircraft to airworthy status. A close inspection revealed that as well as installing the new alternator we’d do well to re-do the cable repairs that had been carried out in Khartoum. While serviceable, they could not exactly be described as examples of best practice. The brackets that the alternator was mounted on also showed evidence of some wear, leading to a little movement that was possible; this could well have contributed to the problems with cables breaking. A call to the engine manufacturers, SMA, confirmed that this issue had indeed been seen on other aircraft.

Before we could complete the installation of the new alternator, Keith was called away for the day. I returned to the Aero Club to book another night’s accomodation. Hopefully I would, at long last, be on my way the following day!

I met Keith at MAF a little after 0700 to finish the installation of the alternator. A couple of hours later everything on the engine was back together, the cowlings were replaced, and one of the MAF staff had even given the aircraft a thorough wash! Keith and I climbed aboard and started the engine; there was still enough battery for this, at least. Holding my breath, I flicked on the alternator; and with huge relief watched as the ammeter needle instantly pegged itself to full charge, and all electrical warning lights were extinguished! Keith got out, and I taxied over to the far side of the airport to run the engine for some time and build up charge in the battery again. It took a good half hour, but eventually the ammeter returned to normal levels and I parked up at the Aero Club to load all the gear and finalise the flight plan.

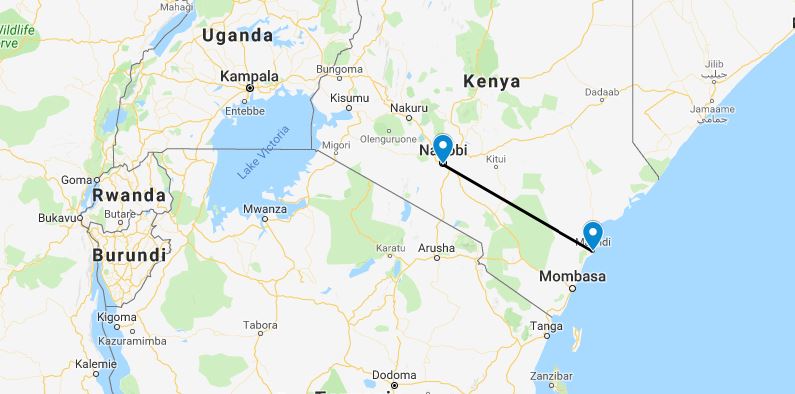

At around 3pm, I taxied to customs. I’m not sure why this was required for an internal flight, but they insisted I go there anyway. In the end all I had to do was walk out of the arrivals gate, back in the departures gate, hand a copy of the manifest to a customs agent, and get straight back into the airplane. There seemed to be something of a lull in traffic and after a short wait while yet another Cessna Caravan departed I was on my way to Malindi, to meet up with Sophia. I followed the VFR departure route, which was helpfully marked on our charts this time, and climbed to 9,500ft to clear the hills east of Nairobi. That done, I descended to 1,000ft to head out across the plains, hopeful of spotting animals! I saw, exclusively, a great many cows.

The flight to Malindi was around two hours. I arrived at the airport shortly after a Cessna 172 arriving from the south, and flew final approach with the African coastline just a few miles away off my left wingtip. So far we had visited the northern, western, and eastern coasts of the continent; just the south left to go! The small apron was almost deserted, and within a few minutes of arriving I’d had some help to push the aircraft back onto the grass and was being greeted by Sue, one of Sophia’s friends who lived nearby. We arrived back at their house at about the same time as her husband Damian, and a few minutes later Sophia turned up after her day of medical work in Mombasa.

Although originally from Britain, the couple had now lived in Kenya for well over a decade, working in the hotel industry. There was, in fact, quite a community of expatriates in this small tourist town, primarily British and Italian. That evening we visited the local bar, located at one of the hotels along the front, where we were introduced to many of the other expats; an excellent meal was also available! With the tide well out I set out for a walk on the beach, but came across such a huge number of small, fast crabs that I retreated due to a certain concern, no doubt misplaced, about finding them running up my shoes and clawing my legs.

Given that it was the weekend we elected to remain in Malindi for another day. There would be no point in turning up in Arusha just to spend Sunday waiting around. We had a late morning, and at around 1030 we joined Sue and a few others for a walk down to the beach and out along a large sandbar that was revealed at low tide. The beach was busy but not crowded, largely with Italians from a nearby hotel. A couple of sightseeing boats arrived and disgorged their passengers before anchoring, and their crews taking a break. The views from sandbar were beautiful, the water warm and clear; just as well, as the tide was coming in and our return to the beach involved as much swimming as it did wading.

After a lunch of pasta and salad Sue gave me a lift up to Damian’s hotel, accompanied by David and Simon, two Brits in their twenties. David was working on a farm in the north, and his brother, an army captain, had come out to visit for a while. We had been informed that the hotel had sailing catamarans for rent, and were looking forward to an afternoon of sailing and snorkeling. On arrival we found that the catamarans had been a little over-hyped, and were in fact bright yellow roto-moulded “funboats”. With three people squeezed on their buoyancy was a little questionable, but we set off out to see anyway with David cheerily humming “Yellow Submarine” as we went.

Once two occupants were turfed overboard to snorkel, the boat regained most of its performance, and it was at times possible to even get it surfing down the large swells that were rolling in towards the beach. We took it in turns to swim and sail; I saw absolutely nothing underwater apart from seaweed, but Simon spotted a little shark. It was small enough to cause him to call us over to look, rather than to try and get out of the water, but unfortunately by the time we got there it had vanished. Simon and David set out to the little rocky island (more of a rock, in fact) to inspect it and before too long I was being called over to remove them from the area. The island was covered with large crabs which were apparently “pretty nasty”.

That evening we were taken out for dinner, along with 10 or so others, on a dow belonging to another one of the expat social circle. This was usually run as a business taking tourists for night cruises. The dow was surprisingly speedy and we headed up the creek away from the ocean under a brilliant full moon. Dinner of steak and accompaniments was cooked on board, and even Pina Coladas were available! After a few enjoyable hours we motored back upwind to the jetty, and headed home.

We were at the airport by 0900 preparing to finally get underway again on the trip. The original plan had been to fly via Mombasa in order to clear customs and immigration but it turned out that, with a short wait, someone could be summoned to Malindi to handle these formalities and save us a stop. We refueled and took care of the paperwork while we waited, and once the immigration official arrived it was just a few minutes before we could be on our way. The first leg would be a two hour flight to Kilimanjaro airport, the international airport just 30 miles from our final destination of Arusha.

We set off along the coast south, as we wanted to fly past the village we’d spent the last couple of days in before we turned inland towards Kilimanjaro. Approaching it, we descended to a few hundred feet and flew low and slow over the beach to take photographs of the house and surroundings, and also try and spot the family! We failed to do this, but later heard that they had been out walking and had clearly seen us pass by; we just hadn’t spotted them waving!

Turning inland, we climbed up to 8,500ft to stay above the scattered cloud layer. The winds were favourable and we cruised at 130 knots ground speed. After an hour or so, Kilimanjaro came into view in the distance. Approaching the Tanzanian border the clouds cleared away and Sophia spotted a herd of animals down below; a quick descent revealed them to be a huge quantity of wildebeest. Trotting along to the side of them were a group of 5 or 6 elephants! Well pleased with this sighting, we had flown only another 20 miles or so before we came across more elephants, but this time a herd of 100 or more animals. Despite the heat and the turbulence down low, we lingered for a while watching them before continuing to Kilimanjaro airport.

Kilimanjaro was not a busy airport. We quickly procured aircrew visa for the country, and having exited through the arrivals hall immediately re-entered at the other end of the airport to file our flight plan and pay the considerable navigation and permit charges. “Navigation” charges are one of the biggest rip-offs in African aviation; almost no air traffic control is offered, and in those places where it is available it is often of a very poor standard. It can certainly not be considered decent value for money! Fees paid, we relaxed by the aircraft for some time to consume the sandwiches that Sue had kindly sent us off with, and chatted with some local pilots who were very interested in our unusual diesel engine.

The flight to Arusha took only twenty minutes. This local airport, much smaller than Kilimanjaro, was nonetheless much busier and the apron was packed with Cessna Caravans and other light aircraft. We were parked down one end near the fuel pumps but warned to leave the parking brakes off as they would most likely have to move the aircraft to deal with future traffic. As we made our way out of the terminal, intending to locate a taxi, we were approached by a western gentleman addressing us in French; he had spotted our aircraft registration. This turned out to be Ben, a Belgian pilot volunteering for a local charity, the Flying Medical Service. They operated two Cessna 206s as air ambulances, as well as visiting villages for vaccination campaigns. Ben introduced us to Pat, the director, and we were soon offered accommodation in their compound which we gratefully accepted.

Pat was busy replacing an antenna on one of the 206s. We set to work helping him; as a result of a recent accident that had wiped out the other 206, he was temporarily unable to lift any heavy items. The work took a half hour to finish, and we then all piled into the little Suzuki Jimny and headed back to the compound; Ben had gone ahead on his bicycle, a brave man in the heat and surrounded by African drivers! At the compound we met Elsa, an American volunteer, and Kylie the Australian administrator for the group, who warmly welcomed us and set up a room for us in the main building.

That evening we joined the FMS crew, and a number of other expats, for dinner in the city at a Chinese restaurant. While not particularly traditional cuisine, it was apparently one of the very few places where you could have a meal in less than four hours; Tanzania is, it seems, notorious for incredibly slow restaurant service.

Click here to read the next part of the story.