Round the World – Australia 2, Part 1

I exited the airport fence, and headed for the control tower. I’d had a message that the tower controllers wanted to chat with me on arrival; usually this is a bad sign, but on this occasion they just wanted to discuss my planned flight the next day, coordination with Auckland Oceanic control, and so on. We spoke for a while up in the tower, and once done one of the controllers was kind enough to give me a lift to my motel in his van full of wood.

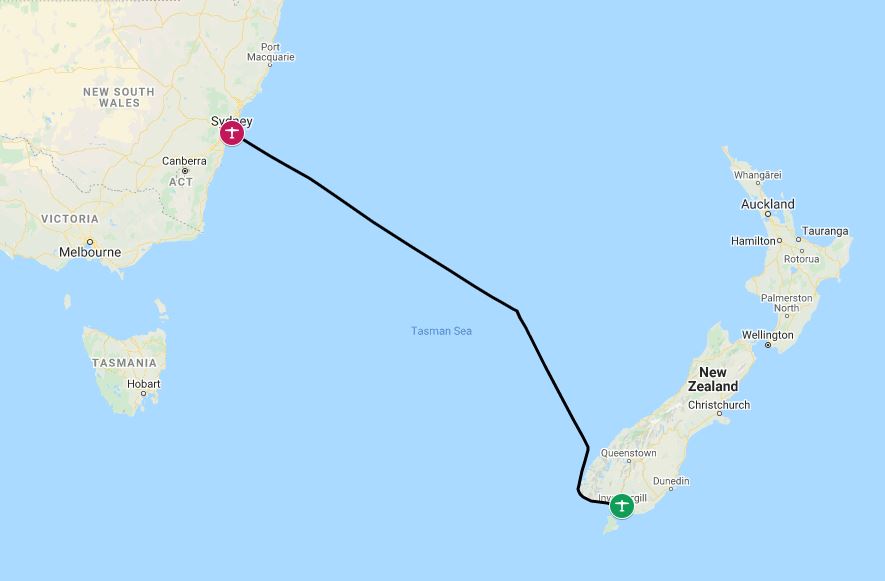

I hadn’t paid too much attention to the longer range weather forecasts, having decided to concentrate on my flights through the South Island and then, after getting to Invercargill, wait for the right moment to depart. The prevailing winds across the Tasman sea blow from west to east, especially this far south; my route sat firmly within the “roaring 40s” where strong winds circle the earth with almost no land masses to disrupt them. Bad weather in this region is common too, so I was prepared to spend a few days at least waiting for the right moment.

Sitting in my motel room I opened up the “Windy” app, and my heart rate spiked. Moderate winds were forecast to be blowing across the Tasman the following day, on my planned route, from east to west. This was rare good fortune and I had to jump on it before the weather patterns changed back to normal and I ended up stuck. The flight to Australia was now set for the following morning; I had dinner, bought some supplies for the flight from the supermarket across the road, filed my flight plan, and settled in for as good a rest as I could manage given the excitement I was feeling. It was finally time to do some proper long distance flying again.

When I woke the next morning, ceilings were low and light rain showers were blowing through. A stiff breeze was blowing from the west. I was not disheartened, however, as the forecast from Windy had included these aspects; the clouds and showers were local to Invercargill, and the wind strength and direction once around the southwest tip of New Zealand would be far more favourable. I arrived at the airport a little after 7am, ready to organise fuel and take care of the customs and immigration formalities. The fire crew let me in through the security gate and I headed over to Planey to begin.

First task, after removing and storing the cover, cowl plugs and so on, was to refuel. Two options were available; buying fuel through Stewart Island Air, or buying through the flight school, Southern Wings. As the flight school was not yet open, I caught a lift with a very helpful airport fireman up to the terminal and chatted to the guys from Stewart Island Air. They said they’d be happy to help, and let me know that they’d be out soon to assist.

The fireman dropped me back at Planey, and I spent a bit of time re-organising the baggage and other items. Anything not needed anymore was consigned to the waste bin. During this time the man from customs and immigration arrived; the flight school was just opening up, so we met inside to take care of the paperwork. He was a friendly and helpful chap, and everything went smoothly. Stewart Island Air had not shown up, so I asked Southern Wings for help and they very generously sold me AVGAS at cost. This saved me a few hundred dollars compared to buying through the commercial operator! Soon I was saying my goodbyes to the Southern Wings crew, and starting the engine, letting the engine warm up as I waited for my IFR clearance.

Before long I was reading back my clearance to tower. Despite being on an IFR flight plan, I requested to fly the first leg in visual conditions, taking responsibility for my own terrain clearance. The minimum altitude for standard IFR in this part of the country is far higher than I wanted to fly, due to the presence of the Southern Alps. Staying low would be easier on the aircraft, and also keep me in lower headwinds. This request was approved, and soon I was rolling down the runway and heading west across the Southland coast.

I made my way along the coast at about 3,000ft, through some scattered cloud and the occasional rain shower. The wind was swinging between a direct headwind, and a quartering headwind from the south; I was looking forward to rounding the bottom corner of the country and getting into more favourable conditions. For about 50 miles I was able to remain in VHF contact with Invercargill, and they passed me the frequencies that I’d need to use to contact Auckland Oceanic on the HF radio. For once, I was actually able to talk to them! It felt good to have the HF working at last.

I hugged the coast of Fiordland, turning north to head towards my first IFR waypoint. Flying up the coast, it was fun to see the mouth of Doubtful Sound where we’d been enjoying a boat trip almost a year earlier. This southwest corner of New Zealand is some of the most inhospitable and inaccessible in the country, and I felt privileged to have the chance to see parts of the landscape that most never get to set eyes on. Shortly after passing Doubtful Sound I reached my first IFR waypoint and it was time to take a sharp left, and head out into the Tasman Sea.

It was exciting to be setting off on another long water crossing, as well as a little intimidating. The mountains of the South Island slowly dwindled in size behind me and before long the land was entirely out of sight.

Naturally, it was at this point that the HF radio stopped working. I was calling Auckland, but all that I heard through my headset was static. I remembered the Oceanic Controller that I had met months before in Nelson, and sent him a message through the Garmin InReach; he quickly replied, letting me know that he’d spoken to his colleagues. They could hear my transmissions, and told me to just giving regular position reports even if I received no reply. Technology is wonderful!

I settled in for long hours of nothingness, with the autopilot set to track the flight plan loaded in the GPS. I passed the time listening to podcasts through the Bluetooth feature of the PMA450B audio panel, and snacking occasionally on the supplies I’d picked up the night before. A couple of hours out, I started receiving Auckland’s transmissions again, and the HF worked reasonably well for the rest of the flight. The entire time, I didn’t see a single boat or other aircraft; I might as well have been alone on the planet, were it not for my electronic links back to the rest of humanity. The only variety in the view were the occasionally changing cloud conditions; from clear, to scattered, to overcast, and back again.

Around 100 miles out from the Australian coast, I made contact on the VHF with Sydney. They cleared me to continue along my flight planned route and it felt like no time at all before I started to see signs of civilization; first a ship, and then the coast of Australia itself. It was a very welcome view after all this time over the cold Tasman Sea!

Given the international situation, Sydney airspace was quiet. The controller took the opportunity to treat me to incredible views of the city, directing me to approach from the north straight past the city center. I really felt like I was receiving a proper Ozzie welcome, given the Sydney Opera House and Harbour Bridge visible right out of my pilot side window!

The approach controller lined me up on a final approach for runway 16 right, and handed me over to tower. Little did I know at this point that I was being photographed by a keen spotter, Grahame Hutchison, who runs the 16right aviation photography website and had spotted my arrival on Flightaware. He took some beautiful pictures of my arrival, although I found myself wishing that I had cleaned the aircraft belly before leaving Invercargill!

I touched down on 16 right, and taxied in to park at the FBO. It had been a long haul by most general aviation standards; 8 hours. They brought a van over, and we headed off on a drive around the airport; in COVID times the customs and immigration people would no longer come to the FBO for clearance, but would only operate out of the main terminal.

Tens of Qantas aircraft were parked up, out of use for the time being given the huge drop in travel. At the terminal, we made our way through a health check, followed by immigration and customs, before returning to the van. It was bizarre to walk through the arrivals hall and not see another soul, after being here in normal times less than a year earlier.

Back at the FBO I carried out the flight planning for my next leg, while one of the staff very kindly took my debit card across the road to McDonalds and bought me lunch (I was not allowed to leave the airport, a peculiarity of the COVID restrictions). As soon as practical, I was on my way again, taxiing out and departing to the south. I still had a very long way to go.

The weather was lovely for a relaxing cruise down the Australian east coast. Relatively quickly it became clear that I was not going to make it to Hobart comfortably with the amount of fuel that I had remaining; while it should have been enough to make it, there were not enough alternates in the hundred miles before Hobart to make me happy, and I didn’t want to end up stuck somewhere overnight. I selected Mallacoota as my fuel stop, in the COVID-affected state of Victoria – while no travel was allowed to states outside of Victoria without quarantine, if you’d been in Victoria, an exception was written into the rules for transit stops such as refueling. The fuel was self-serve, and I didn’t see another soul; I was soon on my way again as night gradually descended.

I donned my life jacket for the final significant water crossing of the day, over the Bass Strait to Tasmania. It was fully dark by this stage. After about an hour, the lights of Tasmania’s coastal towns began to appear. I was getting quite tired by now, and it was great to have visual confirmation that I was nearly at my destination! Hobart tower cleared me straight in to land, and I followed the “follow-me” truck to parking.

While my final destination for the day was actually the airport of Cambridge, just two miles away from Hobart airport, COVID restrictions meant that I had to arrive into Hobart and be met by biosecurity staff. I ended up waiting for over an hour, because biosecurity were driving from meeting a ship some distance away; it was not entirely clear why they couldn’t just drive to Cambridge instead and meet me there, but this suggestion was rejected. I spent the time texting my friend Ollie (who’d flown the 206 with me the previous year, and would be hosting me in Hobart), and the night manager at the Hobart YHA where I had booked a room. I wanted to ensure that they didn’t lock up before I got there!

Finally biosecurity turned up. All they did was ask me to confirm that the information I’d entered in the online form was correct, and then buggered off. Time well spent. Minutes later I was airborne for the 2 minute flight to Cambridge where Ollie had been waiting (it was now after midnight). He directed me to parking, and then gave me a lift to my accommodation. I was very happy to be going to bed – it had been a day of nearly 14 hours flying, and significantly more hours awake in total!

I slept in late the following day, before Ollie came to pick me up and show me around the city of Hobart a little. Hobart was founded in 1804 on what turned out to be the second deepest natural harbour in the world, and is the second oldest capital city in Australia after Sydney. This fine port soon became one of the main ports supporting southern ocean whaling, and the city rapidly grew into a fairly major settlement. Today the major industries supporting this city of 250,000 inhabitants are tourism, shipping, a variety of heavy and light industry, and the city also serves as France and Australia’s gateway to the Antarctic.

We started out with a drive down to the harbour, where Ollie works on occasion as a pilot of the Beaver seaplane that gives tours for tourists. This was also an opportunity to stop for an ice-cream and enjoy the afternoon sun.

From here we drove up through the suburbs, out into the bush and up the steep road to Mount Wellington. Although at 1,271m (4,170ft) it is only the 49th highest mountain in Tasmania, its position overlooking the city makes it look particularly imposing. On a good day you can see 100km (62 miles) to the west! It was breezy, and significantly cooler up the top of the mountain, but the views over the city of Hobart were well worth it. We even got to see a wallaby!

The day was finished off with an excellent pizza, once we finally found somewhere that could seat us; apparently this was the first nice day of the season, and the whole of Hobart were out and about!

Ollie was busy working the next day, so I had the time to myself. Lacking a car, this was the perfect opportunity to explore Hobart on foot a little. I started off with a visit to the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, which was established all the way back in 1846 by the Royal Society of Tasmania. I was a little concerned when I arrived at the front door to discover signs announcing that the museum could be visited by appointment only – happily, they turned out to be very quiet and made me an appointment for right that moment. In the end, I only saw a few other people inside.

The museum holds a wide variety of exhibits, and states that they hold the broadest collection mandate of any single similar institution in Australia. The collections cover material evidence of Tasmania’s cultural heritage and biodiversity, with a focus on historical, scientific and artistic items.

I spent the rest of the afternoon wandering around the city, checking out some of the historic architecture, and finishing up with dinner from the floating take-away restaurants down in the harbour!

The weather the next day was pretty fine, so Ollie and I took the opportunity to go for a flight in his Piper Cub. This aircraft is very different to Planey, being a small tail dragger with tandem seating, set up for serious off-airport flying. Ollie handled the difficult bits, but gave me the rest of the flying, and we took off from Cambridge and headed off up the River Derwent. The views of Hobart as we flew overhead, low and slow, were magnificent; very different to my arrival at midnight a few days before!

Ollie was taking me up the valley to visit a vineyard location owned by a friend of his, where he had several off-airport landing areas scouted out. I handed control back to Ollie, as there was no way I was going to try and land a taildragger anywhere like this, and there was probably no way that he’d let me! When landing in a field which isn’t even usually used as a runway the importance of the “runway” inspection is even greater than normal and we made a couple of circles low over the area to ensure everything was safe for touchdown. The first paddock we landed in had a teepee set up in it; we wondered if there’d be anyone inside.

Somewhat disappointingly there was nobody in the tent for us to surprise, so we took a few pretentious photographs and took off again, performing a brief landing in one other paddock before heading back towards Hobart. We landed at Cambridge after a low level tour of the city, including a chance to see Australia’s Antarctic survey ship which was moored in the harbour. Now it was time to wash off all the sheep mess thrown up by the wheels during our off-airport landings!

We grabbed lunch nearby before returning to the airport. Ollie had called in a favour and arranged a space for Planey in the hangar next door to his, so we relocated the aircraft and drained the oil ready for the planned oil change, as well as servicing the spark plugs. Ollie made something of a schoolboy error and started cleaning part of the engine with degreaser; and once he’d started, I wasn’t going to let him stop until he’d finished the whole engine!

One of the exhaust gas temperature probes on the engine had started malfunctioning; typically, it was the specific one which I usually used to guide my control of the engine’s fuel/air mixture (a process known as “leaning”). The avionics engineer at Cambridge luckily had a spare, and we took the chance to fit it; he refused any payment other than a few bottles of his favourite wine! No fresh oil was available to refill the engine, so we tucked Planey away inside the hangar and headed back to town.

Over the next few days I busied myself with seeing more of Hobart city. A particular highlight was the “Retro Fudge Bar”, a small café with all different flavours of fudge and other sweet treats. This was not something which I could resist, of course! I also spotted, down a small side alley, some graffiti of a Tasmanian Tiger. This striped animal, with the appearance of a medium to large dog, was driven to extinction by human predation, largely in response to the fact that the tigers were taking livestock. It was, at the time, the largest carnivorous marsupial in the world (a marsupial being an animal which raises its young in a pouch, such as a kangaroo). This sad history was alluded to in the melancholy caption accompanying the image; “All I wanted was a sheepie, just one sheepie…”

I took a walk through Franklin Square, a couple of blocks away from the museum. Sir John Franklin was an Arctic explorer, and former Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen’s Land (as Tasmania was known at the time). Nearby is the Mawson’s Huts replica museum, situated just 200m from the point at which Mawson’s expedition departed for Antarctica. Sir Douglas Mawson was an Australian geologist, Antarctic explorer, and academic, who amongst many other feats was leader of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition in 1912. An interesting aviation connection is that Mawson’s expedition brought the first ever aeroplane to Antarctica; unfortunately due to damage and unsuitability for operation in such low temperatures, it never flew.

During the expedition, Mawson led a three man sledge party to survey King George V Land. This went well, until one fateful day when party member Ninnis together with their six best dogs, most of the party’s rations, their tent, and other essential supplies fell into a crevasse and were lost. The remaining two turned back immediately; they had one week’s provisions for two men and no dog food, and were ultimately forced to use some of the sled dogs to feed themselves and the remaining dogs. Mawson’s final companion, Mertz, died 100 miles from home base, with Mawson returning just hours after the expedition’s ship had left. He was forced to winter over with the party which had been left behind to search for the missing men, before finally being rescued the following season.

Late in the week, Ollie and I took the cub over to the private airfield of Sandfly. On of Ollie’s friends was based there, and had a crate of the oil which we needed for Planey. While there we helped him fit a new battery to his Victa Airtourer (the same type of airplane which Cliff Tait had flown most of the way around the world). As we flew back to Cambridge, he pulled up alongside us on his post-maintenance test flight to say hello!

The end of my time in Hobart was drawing near. Ollie’s friend Paul invited us to join him for dinner one evening at his farm, on a hill overlooking Cambridge airport. At dusk, the grass around the house became teeming with wallabies, many of whom had their young with them, which was a real treat to see for a foreigner like me! As we ate, we made plans for the next day; Ollie and I were going to take Planey for a tour around some of his favourite strips in Tasmania, and friends Mitch and Paul would join us for some of it in the Piper Cub, and Paul’s Maule respectively. Ollie and I said our goodnights and he dropped me back at my hotel; it was going to be an early start the next day!

Click here to read the next part of the story.